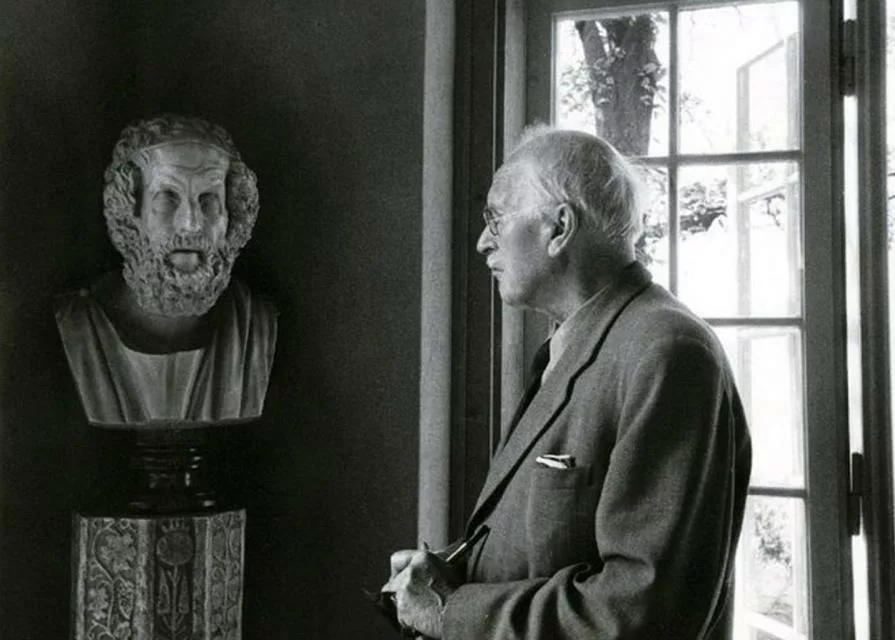

Pictured above: Carl Jung contemplating the bust of Socrates.

“My way toward the truth is to ask the right questions.”

–Socrates

What if, whenever your student or child made a statement, you imagined them saying at the end of that statement: “Those are only my initial thoughts.” Then, you might naturally want to learn what their next, more developed thoughts were. You might want to probe them. Enter Socrates.

If there were a patron saint of education, it would be Socrates. Socrates is to teaching what DaVinci, Copernicus, Darwin, and Einstein were to their respective fields. Henry David Thoreau, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr., all evoked him from their jail cells, so liberating is his approach. The Socratic method of teaching is so basic and so essential to teaching that one cannot master teaching as we know it without it. What’s more, one could actually rely solely upon this method, ignore almost all else, and excel beyond all other teachers. And it is actually simple (even though I have spent 45 years barely mastering it).

When I say simple, I do not mean you have to go barefoot and wear a chiton (the Greek toga). I mean it relies on the simplest possible questions. Let’s start with this one:

When was the last time you experienced great listening?

The heart of Socratic method is great questioning, predicated upon great listening. When we experience these, both the teacher and student grow wiser, together—this is the mark of great teaching. When we experience great teaching and listening, we are experiencing friendship and love.

Parents, consider this: when students feel able to meet parent expectations, they are less likely to be worried and stressed about their schoolwork and less likely to suffer from physical symptoms of stress.

What if your only expectation were to understand your child’s thinking better?

Here is help. Here are my top tips from Socrates, which you are free to share with all the parents you know:

1) Challenge authority: The first amazing thing about Socrates with respect to parenting is that rather than feeling shocked and appalled when our teens challenge authority, Socrates showed us that this was a gold standard indicating the highest readiness to learn. Expect smack! Embrace polarization (a phrase that sounds easy but took me many years of concerted work). Recognize your teen’s challenging comment as a sign readiness to be probed—because, first and foremost, Socrates called upon all of us to think for ourselves.

2) We must never settle for the mundane: So, your teen has pushed a limit, or has gone mute, or has uttered the superficial, or has uttered the outrageous. The Socratic imperative is to ask: “What question could I ask now to elevate this conversation from the mundane, the shallow, the dull?”

3) Admit no right answer. The whole point of Socrates was to question “conventional wisdom.” If we are going to be great Socratic teachers, we cannot allow ourselves to accept the first answer our students offer up. We must never ignore all that lies beneath every, single first answer we will ever hear. Nor must we rely upon tradition or the standard, expected answer. We are looking to push our student’s mind further and beyond! The extraordinary is in there if you probe. Believe it. Follow Socrates …In Socrates’s world, The Parthenon was a temple honoring the city’s patroness, the goddess Athena, and it overlooked the thriving, bustling city marketplace and port area called the Acropolis. The leading thinkers, artists, architects, and writers were all drawn to Athens: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides … it was the center of the Western world. Pericles lectured there. And yet, as the great historian Toynbee noted, “The finest flower of Athens during this half century was not a statue, building, or play but a soul: Socrates.” Some found him almost painful in his constant pushing at people’s statements, but he believed his prodding would bring forth better ideas, and they did. In this pushing, Socrates gave us the Socratic method. This method contains the ultimate gem of human optimism:

We all can be awakened.

This is the very gem which determines which teachers will be well remembered, and which are ill-remembered or forgotten altogether.

4) Offer no conclusions, insights or tenets of your own: the Socratic teacher interrogates students about their own conclusions. In this way, the Socratic parent does not force their children to repeat their own life and thoughts, but challenges them, compels them to search for their own self-knowledge, their own lives. It’s fearless parenting.

5) Probe for clarity, not rightness. Not just for our children or students, but for ourselves, it is true that the ideas we find in our minds at the start of our discussions are, more often than not, confusing, unclearly formed, surface thoughts. There are reasons we have put those thoughts at the surface. They often mask all sorts of underlying assumptions and unspoken theories. The Socratic teacher asks, “Why do you think that?” “Are you sure that idea is finished?” “Is that as clear as it could be?”As any Grauer School teacher has discussed and practiced 1000 times, the great teacher does not probe for “the right answer,” the great teacher probes for clarity.

6) Find your own Socrates. We all have a teacher in our life for whom we carry the torch. For almost all of us, we do not carry that torch because we thought that this teacher of ours was so smart. We carry it, rather, because it is that teacher who made us realize that we were so smart.

The great philosopher Fredrich Nietzsche noted, “Socrates teaches you how to listen …he divines the hidden and forgotten treasure, the drop of goodness from whose touch you go away richer, opened, less sure, perhaps, but full of hopes that as yet have no name.” I would call that treasure “clarity.” I would call it “inspiration.”

7) Question and keep questioning until your student arrives at their own core values. The first time you ask “why” or for more clarity, you are liable to get more explaining, or logic, or even defensiveness. Socrates regularly questioned his friends and students until they arrived at something deeper. If you want to help someone become “wise,” start with the “whys.” Even if you have to ask “why?” 40 times, eventually you can get to the core values that cause your student to say what they do. Until you get to their core values, your student will never have clarity of thought. What’s more, until you get to those core values, you will not help students to change their minds, or open their minds, or have a larger vision.The Socratic parent will get to those deeper thoughts and values. Carl Jung called it the shadow self—everyone has one. We have unconscious thoughts, unprocessed and raw ideas, fragments, fears disguised and not faced, unstructured images, all coming out of our mouths in quickly formed conversational expressions, all happy to masquerade as supportable opinion, knowledge, and facts. Socratic teaching digs down beneath all this for the golden rules.

The student leaving the great Socratic lesson knows, or feels, “I took steps to care for my soul.” There is no better human knowing or feeling. Naturally, these are not multiple-choice questions and Socrates certainly would have been terrible at the SATs. Every answer could be challenged until those challenges reached down to a core belief. This core, this inspiration, is often devalued at schools. We are told to follow our bliss, but we can only do this by our efforts to reach that core. “Notwithstanding his maieutike (“art of the midwife”), Socrates humbly obeyed the small voice from within,” said Jung.

No educational scholar would dispute that Socratic teaching is the best way—but it is not workable in a world of overgrown, standards-driven schools and, sadly, many teachers in those schools have given up on the Socratic method.

8) Slow down the inquiry. We are not racing to the right answer. We’ll never know a right answer unless we become skilled in exploring alternatives. In this way, we are not only exploring alternatives, we are finding truth, purpose, trust, and even bliss and love. You can take off your shoes now.In days of joy but also days of extinction, wildfires, lies and loneliness we might be able to slow down the inquiry and discover that a radical change of heart is possible when we probe for clarity. Socrates was willing to drink hemlock and die for this. Those are only my initial thoughts.

Recent Comments