The most comprehensive coverage of small school benefits there is.

Download this whitepaper:

Subscribe to Small Schools Coalition updates to receive a free PDF version of this research.

Correspondence concerning this whitepaper should be addressed to the author, Stuart Grauer, at The Grauer School, 1500 S. El Camino Real, Encinitas, CA 92024. Email: stuart@grauerschool.com.

Abstract

This paper is a review of the literature on the benefits of small (or smaller) schools, as compared to large- or middle-sized schools, in six key areas that are of national concern and of concern to every parent and school leader: (a) safety, (b) teaching conditions, (c) academic performance, (d) culture of connection and inclusiveness, (e) learning choices and curriculum, and (f) costs of schooling. Research has shown small schools have very strong advantages in all areas, except for cost. The issue of cost is inconclusive and in dire need of additional research. Based on the areas of concern, the author surmises if only schools of 350 students or fewer were considered, U.S. schools would rank at the top of any international ranking. Various strategies for breaking down schools are provided. The essay concludes with a recommendation for new forms of school evaluation and new performance standards that are better predictors of U.S. prosperity.

Small Schools Whitepaper: A Meta Study on the Benefits of Small Schools

“I spent years where I did not have a meaningful conversation with a teacher.”

– Sal Khan, Founder, Khan Academy

“Smaller, more intimate learning communities consistently deliver better results in academics and discipline when compared to their larger counterparts. Big schools offer few opportunities to participate.”

– J. Matthews, Education Reporter, Washington Post

Amidst a steady hundred-year U.S. trend toward increasingly large secondary schools, this paper focuses on the benefits of small schools. There are various myths distorting collective viewpoints about what a school should be, and this research found even more. There is an historic gap of knowledge on the benefits of small schools, and this research includes a dearth of information on benefits of the nation’s large schools: the consolidated, comprehensive school model that predominates in our nation.

The historical rationales for consolidated, comprehensive schools—economies of scale, social equality, and increased program offerings—are widely known (Nguyen, 2013); however, these assumed benefits have not been verified and, in weighing large schools against small schools, all three of these rationales are questionable or outright false. The prevalent, large-school model evolved very gradually and was not the result of a comprehensive plan. There is not a single place or point in time where a threshold was crossed, and old ways were not working. Of course, we never see a tree growing. Tried and true presumptions about the U.S. schoolhouse have been running on hyperbole: myths mistaken for reality. No one individual is to blame, but schools have grown too big for most kids and teachers.

In this paper, we provide a review of the literature on the benefits of small (or smaller) secondary schools, as compared to large- or middle-sized schools, in six key areas that are of national concern and of concern to every parent. In Part 1, we focus specifically on the first three areas: (a) safety, (b) teaching conditions, and (c) academic performance. In these areas, there is little disagreement that small schools do better than large schools do. Part 2 of this paper focuses on the basics of three more small school benefits: (d) culture of connectedness and inclusiveness (including equal opportunity for underserved groups), (e) learning, curricular, and extracurricular choices, and (f) costs of schooling. These areas deserve special consideration because each of these has, for a good many years, been taken on faith as a benefit and justification for large schools, to the detriment of many. Part 3 considers deeply held but often distorted myths about what secondary education should is like, which tend to hinder imagination and misrepresent the reality of school life for millions of students. We then draw some conclusions and make recommendations.

Part 1: What Is a Small School? Small and Smaller

Our review of the literature on small schools and the first draft of this whitepaper began in 2002 as a simple numbers game and has proceeded with the collaboration of five research associates through the years in an effort to capture the essence of small schools.

There has been little agreement on what small means. We found small to be used variously as an absolute enrollment number and a relative number. For this paper, we define small schools as those with an absolute number of fewer than 400 students (Grauer, 2012c); however, because the field is lacking in consensus about such matters, we often had to draw conclusions about small schools based on their substantially “smaller” size (i.e., their size relative to the schools to which they are compared). Typically, smaller meant at least 500 students fewer than the comparison schools, though many medium-sized schools, typically of sizes of between 500 and 900, were not useful in drawing comparisons, as those schools are neither small nor large. For example, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES, 1998) found schools with more than 1,000 students had far higher rates of violent student behavior than schools with fewer than 300 students, and teachers and students in small schools were far less likely to be victims of crime. The entire range of schools with 300 to 1,000 students was cut out of that study, so a robust comparison could be made (Bingler et al., 2002).

Another issue that has hampered decisive research in past years is that small schools are not always easy to identify operationally or with respect to governance. They include private college preparatory schools, parochial schools, charter schools, schools within schools (SWSs), smaller learning communities (SLCs), rural schools, magnet schools, home schools, and any number of other such configurations other than “comprehensive.” For better or for worse, if its goal is to provide full services for every kind of learner, it is not likely to be a small school.

Part 2: The ABCs of Small School Benefits: A Brief Review of the Literature

Research on small school benefits has thickened over the past three decades. The literature has explored hundreds of small schools, plus various site visits. We reviewed many research studies, quite a few of them metastudies, which reviewed earlier studies. We were able to access a vast amount of information, and our conclusions were drawn based on this breadth and depth of information. For instance, we considered the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory’s well-known review of more than 100 studies and evaluations, wherein small schools author Cotton (1996) noted “…small schools to be superior to large schools on most measures and equal to them on the rest. This holds true for both elementary and secondary students of all ability levels and in all kinds of settings” (p. 11). Bearing out Cotton’s work, Wasley and Lear’s (2001) study of students in 90 small schools showed significant improvements in behavior and achievement, greater teacher connection with parents, and more teacher opportunities to collaborate with other teachers. Haller (1992) included data for 175 rural high schools and suggested creating larger institutions will increase student misbehavior. New York City generated findings on 105 small high schools, showing students, mainly in Brooklyn and in the Bronx, from 2005 to 2008, had substantially higher graduation rates than their large-school peers (Bloom & Unterman, 2012). In the following subsections, the benefits of small schools are reviewed from various perspectives, including safety, teaching conditions, academic performance, culture of connectedness and equal opportunity on campus, learning choices and curriculum, and, perhaps the most controversial, costs.

Safety: A Moral Imperative

“Compared to larger schools, students in smaller schools fight less, feel safer, come to school more frequently, and report being more attached to their school.”

– Joe Nathan and Sheena Thao, Smaller, Safer, Saner Successful Schools

However positive and efficacious the literature shows small schools to be for student learning and opportunity, our findings on school safety are impossible to disregard, and we feel a moral imperative to disseminate them. Small schools are safer, regardless of environment: urban, suburban, rural, etc. (Cotton, 1996). Across the country, rich or poor, small schools are safer places for children. Even the earliest research on small schools showed a stunning difference with respect to safety, violence, and vandalism. The NCES (1998) noted marked reductions in teacher and principal reports of incidents of fights, weapons, and other forms of violence in schools of 350 or fewer students, as compared with reports from schools with 50 or more students. Small schools report fewer fights and no incidents of serious violence (NCES, 1998). Through years of surveying, we found one common denominator: smaller school size has consistently related to stronger and safer school communities (Franklin & Crone, 1992; Hamlin & Li, 2020; Oxley, 2004, 2007; Nguyen, 2013; NCES, 1998; Zane, 1994). Greater safety in small, versus large, schools has been illustrated in a wide variety of types of incidents, including robbery, vandalism, possession of weapons, verbal abuse of teachers, use of illegal drugs and alcohol, and widespread disorder in classrooms (Nathan & Thao, 2001).

The push for smaller schools took on a greater sense of urgency after the horrific 1999 shooting at Colorado’s Columbine High School (and subsequent shootings; Raywid & Oshiyama, 2000). Many observers were and still are convinced that Columbine’s large size—almost 2,000 students in a rather enclosed campus compound—created an atmosphere of isolation and anonymity for some students, particularly outcasts like the two murderers (Hill, 2011). After the Columbine incident, Colorado Governor Bill Owens formed a commission to assess how law enforcement, school officials, and others responded to the shooting and to identify the key factors that may have contributed to it. The 174-page report acknowledged, “The task of coping with school rage” (Hill, 2001, para. 17) is difficult at large schools, where students “tend to feel marginalized and less a part of a school community” (Hill, 2001, para. 17), than students at small schools feel. The commission concluded, “It is difficult for administrators in large schools to create a supportive atmosphere for students” (Hill, 2001, para. 17).

Violence in many forms, ranging from passive and emotional to physically dangerous, is no longer difficult to find on medium- and large-sized U.S. campuses. For instance, among girls who responded to a 2011 survey, 56% reported being harassed over the preceding school year, as did 40% of boys (Anderson, 2011). The Creating Safe Schools: Examining High School Student Perceptions of Their Physical Safety at School report is based on findings gathered in a survey of 10th- through 12th-grade students who took the ACT in October 2018 (Croft et al., 2019). Its findings were that safety varied, depending on the size of the school attended, with students attending smaller schools being more likely than those from larger schools to report feeling safe. The ACT recommended federal and state funding be provided to expand and promote the availability of school mental health services.

Another well-known safety issue is higher rates of drug use in large, inner-city schools of historically underserved populations, but there is a swept-under-the-table parallel: in San Diego, as well as its well-to-do suburbs, the runaway recreational drug of choice for teens is heroin, which is in abundance. Comparatively speaking, safety issues and risks do not substantially present themselves on small campuses (Cotton, 1996; Hill, 2001). Nathan and Thao (2001) explained, “Students at large schools are more prone to be alienated from their peers or engage in risky behavior” (p. 1). Once again, the previous references are a small sample among a good many more research findings. It is impossible to dismiss school size as a powerful and fundamental indicator of safety for U.S. children, and unconscionable to disregard the “costs” of this loss of safety, however difficult they are to grasp and affix.

A final school safety concern is bussing, a large school problem, caused by the relentless consolidations of schools nationwide; it is not a part of the small school experience. The topic of bussing warrants its own whitepaper, so we will offer just a few items related to school safety. Forty-seven percent of public school students use the bus to travel to and from school, and violence aboard is increasing in recent years, along with a decrease in the feelings of safety among student riders (Chen, 2022; Simone, 2016). Many children experience fearful social conditions on long, unsupervised rides (Klonsky, 2002).

What’s more, research has shown that due to diesel emissions, children who ride busses are more tired when they get to school and that they have more trouble concentrating than students who are not bussed. Fine particulates from bus exhaust are more likely to impair the health (triggering asthma) and attention spans of students, and low-income children are the prime targets (Mernit, 2022).

Teaching Conditions

“Small schools have been shown to have the conditions necessary for improvements in professional climates.”

– Jennifer Husbands and Stacy Beese, Review of Selected High School Reform Strategies

Though a great many large-school teachers are, of course, passionate about and masterful in their work, all surveys we found on this issue showed small schools to be more satisfying to teachers than medium and large schools were. In a review of the literature, Cotton (1996) found studies on teachers and administrator attitudes demonstrated findings that favored small schools.

Research on organizational behavior shows the small environments yield a sense of connectedness in smaller, more intimate organizations (Kaufmann et al., 2018; Logan et al., 2008). Small-school teachers reported a stronger professional community than teachers working in other high schools. There appears to be increased ability to build a coherent educational program for students between disciplines and across grade levels. There is less departmental stratification in small schools, so teachers more naturally collaborate (Lee & Loeb, 2000; Oxley & Kassissieh, 2008; Wilson, 2006). Along with the smaller size of the faculty, small-school teachers often work relatively easily across departments. Such partnerships shake up traditional faculty segmentation, departmental alliances, and curricular compartmentalization, and all this makes school become a more authentic, interdisciplinary experience for learners.

Academic Performance

“Smaller high schools are more engaging environments and produce greater gains in student achievement.”

– Joe Nathan and Sheena Thao, Smaller, Safer, Saner Successful Schools

We looked into the comparative academic performance of students in small and large schools, something many parents and professionals consider to be of critical concern in school choice. We understand there is some prejudice against or skepticism about small schools by large-school proponents, who claim large schools, by virtue of having more homogeneously tracked and Advanced Placement (AP) courses, would be more rigorous academically. We found an absence of any research showing this prejudice to be justified. Researchers overwhelmingly reported students learned more in smaller schools (Howley & Bickel, 2000; Husbands & Beese, 2001; Lee & Smith, 1997). In Matthews’s (2014) study of the nation’s most academically challenging schools, 40% were schools of less than 350 students, an extremely disproportional distribution in favor of small schools.

Small schools seem to support persistence better than larger schools do (Cotton, 1996). In a study of longitudinal data related to retention in Chicago Public Schools (CPS), Barrow et al. (2015) found that although 90% of students at small CPS schools qualify for free or reduced-price lunch—greater than the percentage at larger schools—they also were more likely to remain enrolled. About 10% of students drop out or leave CPS after each school year, and Barrow et al. found that after 3 years of school, students at small schools were up to 18 percentage points more likely to remain in school into the next year than students at large schools were. They also progressed through grade levels on time more often than students in large schools did.

For standardization mavens, students in small schools (urban, suburban, and rural) significantly outperform students in large schools on standardized achievement tests (Bryk & Driscoll, 1998; Gladden, 2000; Raywid, 1980). Students in small schools also earn more units before graduating high school than other students do (Letgeres, 1999). Students at small schools are more college ready: they have higher grade point averages (GPAs); their reading scores are higher by almost a half-year grade equivalency, when compared to those of their counterparts in large schools; and they have fewer absences (Bloom & Unterman, 2012; Bryk & Driscoll, 1998; Gladden, 2000; Hu, 2012; Nathan & Thao, 2001; Raywid 1980; Wasley et al., 2000).

Teaching style tends to be different in small schools: teachers tend to use a broader range of strategies to engage a wider band of student learning styles (Wasley et al., 2000) and personalize instruction for various students’ needs (Collins & Varney, 2022). Walsey et al. (2000) showed a strong sense of accountability between students, teachers, and parents in small schools. Teachers in small schools set high expectations of students, which lead to high expectations among the students themselves (Wasley et al., 2000). Students’ attachment, persistence, and performance all appear stronger in small schools than in large schools (Wasley et al., 2000).

The Gates Foundation funded one of the most expensive and comprehensive small schools studies (Bloom & Unterman, 2012). They looked at three factors: (a) attendance, (b) college enrollment, and (c) scores on math and reading tests. This study of 21,000 students found clear gains in graduation rates, basic skills, and college readiness, based on exam scores. Included in the Gates’s college readiness concept of these small schools were schools with enrollments of around 400 and more; however, close student–teacher relationships, community partnerships, and school themes or charter missions, such as conservation, international baccalaureate, or technology, were factors in college readiness. Over the 10 years of the study, the Gates’s small schools ironically grew in size, often reaching enrollments of around 500, until they no longer fell clearly into the category of schools gaining small school benefits (Grauer, 2015). These are huge claims for which we cite here just some sample references among a great many more, but, as Raywid (2000) generalized, “The value of small schools has been confirmed with a clarity and a level of confidence rare in the annals of education research” (p. 444).

Culture of Connectedness and Equal Opportunity on Campus

Research from the 2022 Challenge Success survey illustrates how smaller schools outperform larger schools in almost all areas of support and belonging, in the eyes of students (Grauer, 2023). These perceptions are mirrored by teachers and parents surveyed, as well. Nathan and Thao (2001), Wasley et al. (2001), and many other researchers have found small schools create communities where students are “known, encouraged, and supported” (Wasley et al., 2001, p. 35) and have increased teacher–student connection. Small schools of less than 400 “demonstrate great achievement equity” (Abbott et al., 2022). Smaller, “communal” learning environments reduce student and teacher alienation, commonly identified in large-school systems, and enhance student engagement in learning. Students report feeling more comfortable and safer in a small school environment, which is easily understandable, given the increased safety of the small environment (Jimerson, 2006; Nathan & Thao, 2001). In sum, the culture of small schools typically revolves around hard work, high aspirations, respectful relationships with others, and the expectation that all students will succeed.

The sense of connectedness in small learning environments is not only felt and shared among students, it is shared by virtually everyone, in particular, with teachers (Saiz, 2022). Research shows in small learning environments, relationships between students and adults are strong, trusting, and ongoing (Saiz, 2022). There is much more advising, formal and informal, something to which almost any small-school student or alumni can attest. These relationships lead to a clearer, safer, more enriched path to graduation and postgraduate plans—and the bonds continue long after graduation.

Learning is more equitably distributed in smaller schools. Large school proponents cite greater social choice and diversity as plusses for the large-school model. They add that big teams and having many clubs promote spirit and opportunities for more students, a complex issue containing political, social, and emotional components, among others. Raywid (1999) revealed that in small schools, students of all types feel they can connect with one another much more readily and openly and with caring adults whom they know quite personally. If well led, a school develops its own, unique culture of belonging and achievement. The true small school offers a greater sense of relationship connectedness and opportunity among everyone, which echoes research on small organizations and communities (Cotton, 1996). Among complex organizations, developing a unique, shared culture is more likely where the organization is small.

We have long looked to schools to be places of equal opportunity across groups. Progressives of the early 1900s started the push for school consolidation, so underserved populations could partake in the benefits available in affluent schools and districts. They did this without considering whether enlarging the school might cause it to lose the very benefits it sought to have shared across ethnic and socioeconomic borders. Movements toward consolidation recurred in the late 1900s, from the 1970s through the 1990s, and schools again surged in size—while complaints of inequality in school have not subsided. While some gains in social justice have been made, few researchers have credited those gains to schools.

A literature review of the sense of connectivity and safety at school led us to probably the most profound findings in all our research: Learning is more equitably distributed in small schools (Cotton, 1996; Husbands & Beese, 2001). Small schools create more opportunities for participation per capita; a larger percentage of students participate, and they participate in more types of activities (Black, 2002). Because small schools need a large percentage of students to fill each activity, they engage a broader cross-section of students, reducing social and racial isolation (Clotfelter, 2002). These are striking findings, given longstanding and almost universal claims that large schools offer more diverse learning and socialization opportunities.

For over a century, few local communities across the land were untouched, if not radically reshaped in their composition and functioning, as a consequence of school consolidation (Grauer, 2012b), yet a primary rationale for the school consolidation movement was to provide equitable access to schooling. We may have done well to organize our schools differently, for instance, keeping small, unconsolidated schools (or SWSs) but mixing their demographics to create the equitable access that policy makers and interest groups have sought. Students who participate in activities and feel connected at school have higher achievement, are less likely to drop out, have higher self-esteem, attend school more regularly, and have fewer behavior problems (Howley & Bickel, 2000). If these are gains the consolidated school movement has sought, we must consider whether a century of consolidations, creating larger and larger campuses, has been a grave miscalculation. The creation of large, consolidated schools appears to have created or perpetuated the problems it was meant to solve.

Small schools have a leaner administrative structure, which results in shared decision with the whole faculty. Decision making is less institutionalized and more flexible, explainging why teachers and students in small schools report feeling a greater sense of efficacy—they really have a say.

In addition, relationships with parents are strong and ongoing. Small-school parents are closer and more involved, a critical factor in student success (Thorkildsen & Stein, 1998). In a large survey of parents of students in New York City schools, Goldkind and Lawrence Farmer (2013) found enrollment was significantly, negatively correlated with parents’ perceptions of communication, participation, school climate, student race, and socioeconomic status. Their results imply that small schools are ideal for cultivating school climates where parents are highly involved.

Smaller schools more readily engage community members in educating students. Internships are much more common, as are classroom and assembly visitors. Small schools with open campuses tend to more frequently engage community members in evaluating curricular exhibits, such as portfolios, or attending student visual or performing arts showings.

In small groups, we sense allies and rivals readily. Though all compassionate people strive to create a sense of the connectedness of all humanity and all creation, we have practical and cognitive limits on how many people we can support, trust, and feel supported by in our daily lives, allowing us to live with a sense of high trust and low threat. The advantages for leaders developing trusting, influential relationships in small groups are manifest. In sum, it would be extremely difficult to dispute this finding: Small schools offer students, teachers, and school leaders a substantially greater sense of connectedness, belonging, and safety than large schools do.

Learning Choices and Curriculum: A Myth Buster

“Increasing school size, especially beyond 400 students, does not typically result in a large increase in curricular offerings.

– Slate & Jones, “Effects of School Size: A Review of the Literature With Recommendation”

It is often claimed that a big school offers more choices in courses and clubs. After our review of the literature, we came to view this as a flawed and reductionist way to view what “choice” really means to today’s student. A powerful but little-known outcome of small schools is that they provide students with more choices in their learning. Large-school proponents have routinely argued that large schools have more clubs, specialized classes, and sports. Indeed, big team sports are a U.S. icon, which is difficult to attack, so before considering the verity of these activities, we first noted an irony, that these features are only marginally a part any high school’s own quality metrics—they are virtually never held in greater esteem than safety or academic achievement, for instance. Deborah Meier (2002), often credited as being a founder of the small schools movement, put it candidly:

“When we talk with school officials and local politicians about restructuring large high schools, the first thing they worry about is what will happen to the basketball or baseball teams, the after-school program, and other sideshows; that the heart of the school, its capacity to educate, is missing, seems almost beside the point.” (p. 32)

Small schools create more opportunities for participation, so a larger percentage of students participate, and they participate in more kinds of activities (Black, 2002; Cotton, 1996). My own observations confirm the research cited in the sections, below, that the percentage of high school students engaged in cocurricular and extracurricular activities is higher in small schools, possibly far higher. At small schools there may not be as many options for teams or honors courses, but a greater percentage of students are on a team or in an honors course; also, a greater percentage of students are in multiples activities (Unterman & Haider, 2014). Small size also makes it easier for teachers to organize hands-on learning opportunities that engage students in rigorous academic work that has meaningful consequences in the local community (Bloom & Unterman, 2012; Bingler et al., 2002).

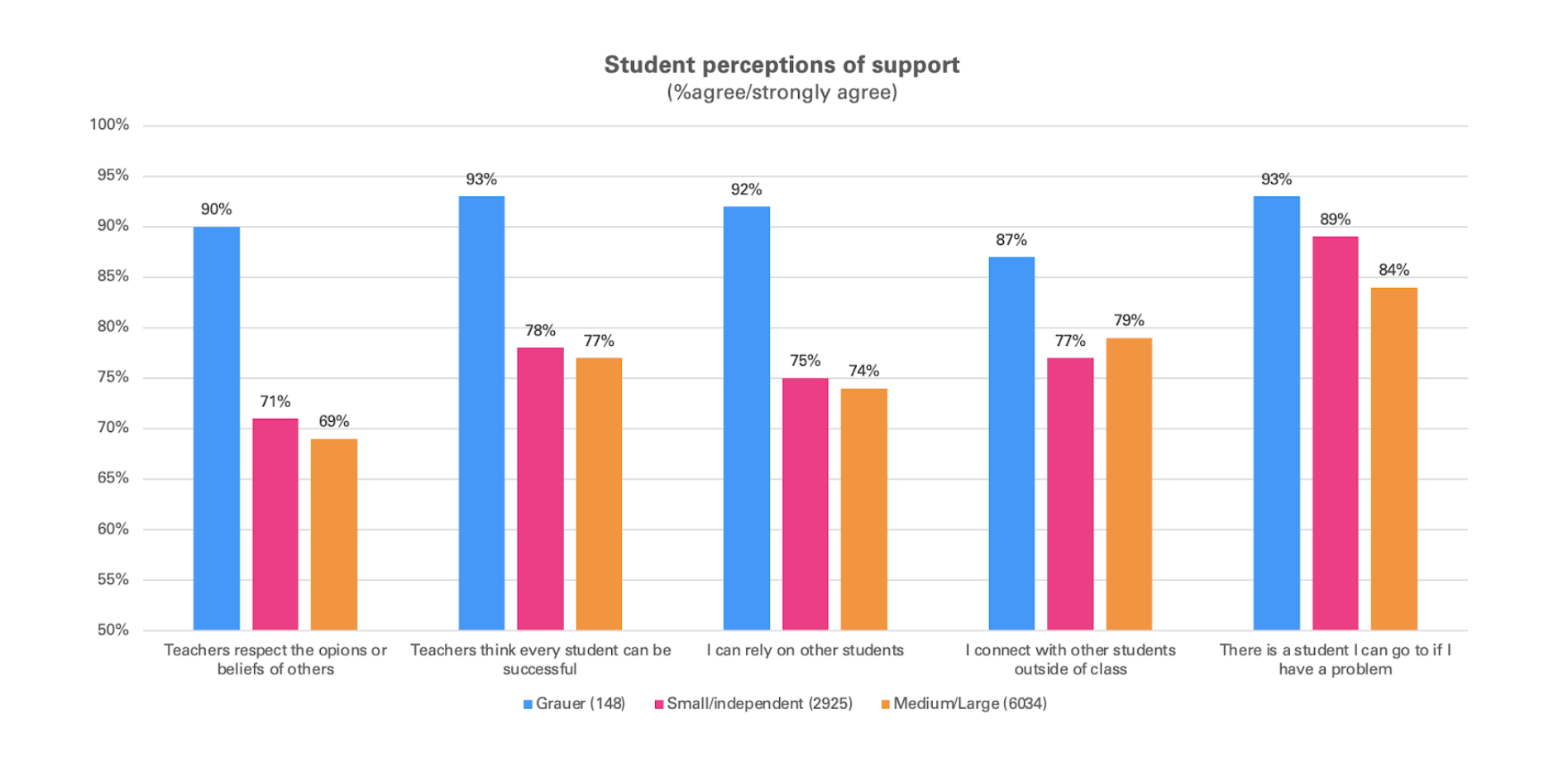

The Panorama Student Survey was developed by researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. The results of a Grauer School Panorama Survey administered in 2021 indicate that smaller independent schools outperformed medium and larger enrollment independent schools in all areas pertaining to student perceptions of support and belongingness.

After an extensive review of the literature, Slate and Jones (2005) found, “Increasing school size, especially beyond 400 students, does not typically result in a large increase in curricular choices. Furthermore … by offering a smaller, more focused curriculum, small schools may actually be more able to maintain quality control”. Barker and Gump (1964) collected data in secondary schools, ranging in size from 35 to 2,287 students. They found increases in school size did not clearly translate into large increases in curricular programming or curricular diversity. The largest schools had 65 times as many students than did smaller schools but offered only twice as many courses. In addition, Slate and Jones found much of the material covered in specialized courses at large schools was being taught in regular courses at small schools. A student who plays year-round varsity sports, enrolls in numerous advanced courses, and manages to stay segregated from the safety issues would appear to be well suited to the large school. This, of course, does not account for most U.S. students.

Figure 1

Student Perceptions of Support and Belonging

Source: Grauer School Panorama Survey, 2021

Small schools are best at responding to individual student interests and needs. The classroom of tomorrow will offer new kinds of access to learning and methodology; interactive distance learning is equalizing course selections for all school sizes. Software allows tutors to meet with students online, so the small school has worldwide resources and outreach. Also, new configurations of choice are emerging. For instance, SWSs might collaborate to establish an interactive television network that allows a teacher in any of those schools to teach students on the network. Small schools also share specially certified teachers for low-demand courses: One school may have a Spanish teacher and another a physics teacher; each teacher can teach a class over the network and provide course access to students in all the networked schools. Interactive distance learning networks are less expensive to build and operate than they are in a new large school; they engage students with technology; and they preserve the advantages of small schools (Hobbs, 2003).

The founding of the rapidly growing SWSs movement is often credited to Mary Anne Raywid (1980), who wrote, “The bigger the school, the more it loses its humanity” (p. 11). SWSs are experimenting with exciting, “best of both worlds” ways of creating SLCs, while retaining large-school resources, such as team sports and high-end technology, which might be too expensive for an individual small school.

If we wish to abandon the traditional U.S. emphasis on liberal arts schooling, sometimes called schooling for a democratic society, and reorient schools to technical and vocational training grounds, sheer numbers of courses may help as well as large schools that offer courses such as metal shop, computer programming, and the Urdu language. A liberal arts education, however, is more student centered, as opposed to content centered, and is more focused on intellectual development. It is the training grounds for entrepreneurship and ethics, and it has never been dependent on a particularly large course catalog.

An exhaustive course and club catalog does not make a good school, nor is it fundamental as a determinant of excellent schooling or even accommodating diverse student tastes and interests: There are too many things that can occur in small arenas that cannot happen in large ones.

Costs

“The ‘cost savings’ of larger schools are only apparent if the results are ignored.”

– The New Rules Project, Small Schools Versus Big Schools

If large schools were cheaper to operate in the long run, perhaps we might have some rationale for their overwhelming prevalence: We could simply say we cannot afford to do more. The issue is there is great uncertainty in knowing if they really cost less. Burkhauser (2017) reported 16% of U.S. public school teachers leave their schools each year, a prime cause for difficulty in collaborating with colleagues. This turnover is a fundamentally large school issue, as the bureaucratization of the profession has forced large-school teachers to judge their jobs based on financial concerns almost exclusively, giving up on the morale, support, flexibility, and connectivity issues that keep small-school teachers in the profession. While there are times when a teacher’s departure is a net plus for the school, most teacher turnover has a negative effect. Replacing a teacher costs between $4,400 and $17,900. The Learning Policy Institute (2017) estimated teacher turnover costs school districts $20,000–30,000 for every teacher who leaves the district.

Taking into account key costly items that are characteristically left out of funding formulas leads to a hypothesis that larger schools, such as those with enrollments in excess of 1,200, may not have produced expected economies of scale that result in better results for less money, except possibly when compared with some medium-sized schools (between 400 or 500 and at least 900)—and not when compared to true small schools (Robertson, 2007). The larger and larger institutions we have been creating have failed to result in an economy of scale or to provide lower per-pupil costs. Formulas found for determining funding tend to disguise tremendous noncash costs associated closely with large schools; some cost are difficult to assess, and some are terrible. Large school increased costs include:

- Increased dropout rates

- Increased violence

- Decreased sense of social safety and connectedness

- Lower teacher satisfaction and higher teacher turnover

- Lower achievement in college

- Less happiness

- Increased commute distances (Andrews et al., 2002)

These costs are seldom considered to be actuarial realities (Grauer, 2021). Happiness is considered because so much research ties it closely to our nation’s overall productivity (Achor, 2012; Conley, 2007).

In addition to these costs, there are greater administrative overhead and external costs, such as the high cost of the federal education bureaucracy. The difference between spending and funding is $97.85 billion or $1,935 per pupil. The federal government provides 7.9% of funding for public K-12 education (Hanson, 2022). The cost of large schools may be similar to that of smaller, more personalized schools, if not higher, in some analyses. Given the stakes, the dearth of thorough research and analysis on the comparative large versus small school costs and benefits is stunning.

Levin and Rouse (2012) said,

“When the costs of investment to produce a new graduate are taken into account, there is a return of $1.45 to $3.55 for every dollar of investment, depending upon the educational intervention strategy. Under this estimate, each new graduate confers a net benefit to taxpayers of about $127,000 over the graduate’s lifetime. This is a benefit to the public of nearly $90 billion for each year of success in reducing the number of high school dropouts by 700,000 — or something close to $1 trillion after 11 years.” (p. 2)

The New Rules Project (2011) summarized,

“Advantages of small schools include improved dropout rates, higher grades and higher rates of college attendance. The ‘cost savings’ of larger schools are only apparent if the results are ignored. If we consider the goal of schools to be improving the lives of students, enabling them to be better citizens, and earning higher incomes (therefore paying higher taxes) then smaller schools are actually much more cost effective than larger schools. All of that is before you even begin to factor in such things as ‘sense of community’ or physical safety.” (p. 1)

Part 3: Educational Myth Busting and the Small Schools Movement

Powerful and often compelling myths about “real” schooling tend to govern collective assumptions about normalcy, and these myths have silently, steadfastly advanced the move to large, consolidated schools and hampered any real proliferation of the small-schools model (Andrews et al., 2022). Cultural expectations about high school are deeply embedded. Wasley and Lear (2001) painted this astonishing picture, paraphrased here: Our collective memory of high school includes nostalgia such as proms, football games, exciting social lives, romance, and first cars. No matter that such memories do not apply to most students. The average high school student does not attend sporting events; indeed the larger the school, the smaller the percentage of student participation in these activities. For most students, the social scene in large high schools is tough and unforgiving, with sharp distinctions made between the small group of social haves and the far larger masses of have-nots. High school memories seldom include a significant academic component, let alone an intellectual one.

Today’s iconic high schools have activities that everyone speaks of with pride, things that the general public now believes to be “the real world”—sacred cows, such as the marching band, the lacrosse team, the boosters. These untouchable activities represent the school’s image and focus on pride. They arduously resist change, even though they serve a relatively small percentage of students and rarely have any connection to the most fundamental aspects of excellent schooling: a focus on student learning, happiness, and the development of shared values (Thompson, n.d.). In the shadows of these myths, kids deal with more drug, self-image, and health problems than the football or cheer teams can accommodate; these are the troubling realities that characterize life in the comprehensive, consolidated, large-school arena.

A profound irony pervades our country: our “postindustrial” nation’s most successful businesses have adopted team approaches, quality circles, small work groups, horizontal management structures, and “tribal” organizing. During this same time, an educational movement toward standardization, rigid management, and misguided concepts of economy of scale keep the small-school movement in its marginal place in federal, state, and district education funding formulas. No football team, no AP catalog, no million-dollar editing room could mean, alternatively, almost no vandalism or violence, few cliques, and fewer dropouts. It is a power trade off, a lifestyle choice, an alternative myth about who we might be as a society. Our vision of U.S. society is incongruent with our vision of community. Myths of normalcy ensure that the average American rarely imagines a real choice.

Institutionalization and Mega-Schools

Small schools compete in the marketplace, in their communities, with their prime stakeholders: parents and community members. Their small size promotes an openness, which makes gatekeeping difficult and minimizes separation of administrators and leaders from constituents. On a campus of 200 people, there is nowhere to hide. In today’s technology parlance, small schools are more “open source”: transparent by design. In the case of private schools, which feature a greater percentage of true small schools, there is nothing more fundamental to U.S. prosperity than their existence: their patrons vote with their dollars. In virtually no other market is such a powerful statement of patronage made: around 10% of the country consistently pays for an expensive service for their children (Murnane et al., 2018; NCES, 2019), a service they know they could get for free. With due respect to large-school iconic activities, such as big teams that only large schools can feature, it is easy to surmise that, if small private schools were free, that 11% could quickly turn into 50% or more, and those factors would seem less sacred. U.S. actual and hidden (and long-range) public high school per pupil, state and federal costs are approaching the private school per pupil costs in some states. Small schools make space for uniqueness and the emergence of individual student voices. There is no known study that has found large-school achievement or safety superior to small, yet we hang on, strapping schools even tighter with funding contingencies that invite mediocrity (McRobbie, 2001).

Advocates of national testing standards for teachers and students believe they put these players on an internationally competitive and entrepreneurial playing field. They may cite competition in test scores and varsity teams as examples of their competitive nature. Unfortunately, this thinking promotes a narrow band of competition, an arena that is just as fenced in as today’s large-school complex. If we wanted schools to compete in things that matter to families, things that will most directly lead toward a happier, more productive country, let schools of all sizes compete with one another on three-dimensional data:

- Student safety (physical and emotional, real and perceived)

- Teacher, student, and parent ratings of trust and liking for the school

- Student and teacher feelings of belongingness and morale in the organization

- College admissions and completion rates

- Student and teacher happiness

Though discussed routinely in news columns, few such measures have made their way into public funding schemes, which tend to eschew both qualitative and long-range orientations. Small schools and most private schools compete and survive all of the previously described critical measures of enduring quality and success. Institutionalization of evaluation leads to one-dimensional evaluation strategies. It is time to shift to 3D teacher and student evaluation. If we are after a strong country of free individuals and entrepreneurship, let us replace the current student testing and data in every school, throw it out, all of it, and replace it with the Milgram Test! Let us see if we are educating individuals. Let us find real standards.

We tend to take long-held state regulations for granted, though they may appear bizarre from the perspective of other cultures. For instance, in 2010, the Chinese government coded into law the management of human reincarnation: In China, one may only pursue reincarnation within state regulations (Richardson, 2022). As preposterous as Chinese regulation might sound to Americans, today’s standardization, testing conventions, size, and bureaucratic regulation of education would take our parents in the 1950s and 1960s equally by surprise, perhaps registering as fearfully socialistic or Orwellian on their radars.

Perhaps it is any large government’s inclination to institutionalize, yet it is the citizen’s role to remain free. Charters, private schools, parochial schools, SWSs: these are all fundamental acts of freedom and entrepreneurship. People naturally seek relationships first, and large institutions have a way of adding limits, lines, and hard edges to those relationships. Here is the heart of the matter: teaching and learning depend on, first, deepening personal relationships. Despite many years of calling our nation’s comprehensive schools “great equalizers,” underserved families do not generally select comprehensive schools: more charter schools locate where populations are diverse in terms of race and adult education levels (Glomm et al., 2005). It remains to be seen what percentage of our populace would choose mega-schools, if they had a choice.

Conclusion

Speaking personally, as well as on behalf of my research associates, and having been responsible for accrediting a good many schools across the U.S. Southwest, I can confess that schools are not always easy to evaluate and measure. I have seen beautiful and serendipitous organizations buckle and fold under the weight of the metrics forced on them—or that they have thrust on themselves in an effort to conform. I understand the need for reliable metrics on school performance, yet I remain acutely aware that forcing artful educating into standardized performance kills both. I believe the answer lies in balance.

As standards mavens, government funders, policymakers, and all the other people who rarely spend a day with students conjure up funding formulas and demands for metrics and standards, we recommend they consider some more dimensions of measurement, such as how safe the kids feel or average daily joyfulness. Why not measure how close the students feel to their teachers? How efficacious they feel? How strong their aspirations are? Let us measure how connected teachers feel to other teachers and to their students and how many alumni visit every year. All of these metrics could be improved predictors of a prosperous U.S. future. Once district and federal officials start measuring more of the things that matter the most, they will find there needs to be a focus on a very different kind of school organization: small schools. Indeed, in aggregate, our nation’s small schools already measure up. Right now, peeling away the bureaucratic veneers of government restrictions would reveal very different purposes than many parents would have in mind for their children’s education.

For the United States, we wish for a preference for accountable individuality. In the Grauer School admissions office in Southern California, we consistently find homeschooled students, who have remained outside of our public system, to be more sophisticated, calmer, and more articulate than are students coming from medium- and large-sized schools. Homeschooled children tend to test higher on standardized tests than do students coming in from large systems that directly prep for such tests. We have learned to bank on this. One small-school director of admissions wrote,

“Every applicant I have interviewed this season has expressed a desire for a healthy working relationship with their teachers. I’m always really touched by this. They all express a desire for teachers who are mentors, who encourage them, even push them, but do not demean them, and who take the time to listen to them and answer their questions. This latter part, answering their questions, is always expressed with great emotion. A lot of these kids are so frustrated by not understanding something, wanting to understand it, and then feeling stranded by their teachers. I find it extraordinary that these young people haven’t given up searching for a suitable learning environment.”

– C. Braymen, personal communication, July 1, 2011

This observation, coming from someone at a quiet, suburban private school, echoes in what might be viewed as the opposite setting. At the conclusion of the study of 105 small schools in New York City, the schools chancellor noted small high school changed lives across every race, gender, and ethnicity, concluding: “When we see a strategy with this kind of success, we owe it to our families to continue pursuing it aggressively” (Hu, 2012, para. 5.)

Specifically, The Times’s report noted: “The latest findings show that 67.9 percent of the students who entered small high schools in 2005 and 2006 graduated four years later, compared with 59.3 percent of the students who were not admitted and instead went to larger schools. The higher graduation rate at small schools held across the board for all students, regardless of race, family income or scores on the state’s eighth-grade math and reading tests, according to the data.”

Small school students met higher state graduation standards. The Times report went further: “Small-school students also showed more evidence of college readiness, with 37.3 percent of the students earning a score of 75 or higher on the English Regents, compared with 29.7 percent of students at other schools. There was no significant difference, however, in scores on the math Regents.” (Hu, 2012, para. 7.)

Many U.S. students are fully engaged in team or large campus activities they love and in challenging course offerings and extracurriculars that draw out their passions, and students like these may never need or consider small schools—but these particular youths are a minority of all of the nearly 20 million high school students.

Jimerson (2006) coined the term the hobbit effect. Jimerson said,

- There is greater participation in extracurricular activities, and that is linked to academic success;

- Small schools are safer;

- Kids feel they belong;

- Small class size allows more individualized instruction;

- Good teaching methods are easier to implement;

- Teachers feel better about their work;

- Mixed-ability classes typical in small schools avoid condemning some students to low expectations.

The aspirations of many school consolidation advocates to integrate schools is commendable, but aspirations have not lined up with results. What if we found out that 100 years of consolidations has produced no clear results? What if we found out that mixing students of diverse neighborhoods into large schools only creates additional grouping and alienation? What if we considered the notion that we may have been practicing consolidation for a full century, and it has largely failed in its main goal? Because small schools need a large percentage of students to fill each activity, they engage a broader cross-section of students, reducing social and racial isolation (Clotfelter, 2002). Could it be that, for the past century, what we should have been doing is creating integrated small schools, rather than lumping everyone into the consolidated model? The implications of this question, to us, are profound and provocative. The answer to this question even might be yes, and we have not researched this issue properly.

We have obviously not taken the time in this document to set forth the many advantages of large schools, as we have addressed a small schools research gap that needs bridging. None of the presented literature and implications are intended as a part of a condemnation of large schools, the districts that preside over them, or the talents, gifts, and dedication that their personnel bring to their students every day. For many students, large schools can be wonderlands of learning and friendship and launchpads to productive, happy lives—but for many, this not so; one size does not fit all. Let the presented literature serve to illustrate that various school sizes have various advantages and that a school can never be all things to all people; our opinion is that this is why they fail.

One conclusion is that, even if for leaders at the top of the hierarchy of large federal agencies, school superintendents, or deans of university schools of education, there will never be a replacement for connecting in sustained relationships (not formulaic “site observations”) with the educators and parents in real communities. Daily, deep conversation with students and parents is the primary source data, and we need still much more. There, in our communities and neighborhoods, conversation is real, and we can access the daily aspirations and fears that people share before trying to “fix” them with sweeping, external, big-money systems and mega-schools that cater for every special interest, except that of a single child looking for quality time with a caring adult. We can access local creativity and energy and honor local desire to be self-determining. Self-determination belongs in all our local communities far more than it does in the hands of a $50 billion-per-year federal bureaucracy.

Parents with children at a very large school may look at this review as a set of signposts pointing to areas where a smaller scale, more personal approach can make a positive difference in their children’s education. Students deserve to be free from worry about personal safety (physical and emotional) and to be confident that their teachers and administrators know them well and can guide their development of skills and knowledge. The United States, in its communities, has a long and rich history in trying various educational methods. Only recently have we stood up against prevailing forces for system institutionalization, which we believe to run counter to that heritage. We need not let this be a long-range trend into the future.

References

Abbott, M. L., Joireman, J., & Stroh, H. R. (2022). The influence of district size, school size and socioeconomic status on student achievement in Washington: A replication study using hierarchical linear modeling [technical report]. Washington School Research Center. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED470668

Achor, S. (2012, January–February). Positive intelligence: Three ways individuals can cultivate their own sense of well-being and set themselves up to succeed. Harvard Business Review, 90, 1–2, 100-102. https://www.di.univr.it/documenti/OccorrenzaIns/matdid/matdid467193.pdf

Anderson, J. (2011, November 7). National study finds widespread sexual harassment of students in Grades 7 to 12. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/07/education/widespread-sexual-harassment-in-grades-7-to-12-found-in-study.html

Andrews, M., Duncombe, W., & Yinger, J. (2002). Revisiting economies of size in American education: Are we any closer to consensus? Economics of Education Review, 21(2002), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00006-1

Baker, B. (2009). Private schooling in the U.S.: Expenditures, supply, and policy implications. Epic Policy. http://epicpolicy.org/publication/private-schooling-US

Barker, R., & Gump, P. (1964). Big school, small school. Stanford University Press.

Barrow, L., Schanzenbach, D. W., & Claessens, A. (2015). The impact of Chicago’s small high school initiative. Journal of Urban Economics, 87, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2015.02.002

Bingler, S., Diamond, B. M.; Hill, B., Hoffman, J. L., Howley, C. B., Lawrence, B. K., Mitchell, S., Rudolph, D., & Washor, E, (2002). Dollars & sense: The cost effectiveness of small schools. KnowledgeWorks Foundation and The Rural School and Community Trust.

Black, S. (2002) The well rounded student. American School Board Journal, 18(6). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234710280_The_Well-Rounded_Student

Bloom, H. S., & Unterman, R. (2012). Sustained positive effects on graduation rates produced by new york city’s small public high schools of choice. MDRC. http://www.mdrc.org/publications/614/overview.html

Bryk, A. S., & Driscoll, M. E. (1988). The high school as community: Contextual influences and consequences for students and teachers. National Center on Effective Secondary Schools.

Burkhauser, S. (March 2017). How much do school principals matter when it comes to teacher working conditions? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(1), 126–145. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737166680

Chen, G. (2022, May). Is your child safe riding the public school bus? https://www.publicschoolreview.com/blog/is-your-child-safe-riding-riding-the-public-school-bus#:~:text=In%20exploring%20the%20specific%20dangers,and%20sexual%20violence%20between%20students

Clotfelter, C. T. (2002). Interracial contact in high school extracurricular activities. The Urban Review, 34, 25-46. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014493127609

Collins, S., &Varney, K. (2022). Small and mighty. National Association of Independent Schools.

Conley, C. (2007). Peak: How great companies get their mojo. Jossey-Bass.

Cotton, K. (1996, December). Affective and social benefits of small-scale schooling. ERIC Digest. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED401088

Croft, M., Moore, R. & Guppy, G (2019, August). Creating safe schools: Examining student perceptions of their physical safety at school. ACT Center for Equity in Learning. https://www.act.org/content/act/en/research/reports/act-publications/school-safety-report.html

Franklin, B. & Crone, L. (1992, November). School accountability: Predictors and indicators of Louisiana school effectiveness. Paper presented at the meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association, Knoxville, TN.

Gladwell, M. (2000). The Tipping Point. Little, Brown and Company.

Glomm, G., Harris, D., & Lo, T-F. (2005). Charter school location. Economics of Education Review, 24(4), 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.04.011

Goldkind, L. & Lawrence Farmer, G. (2013). The enduring influence of school size and school climate on parents’ engagement in the school community. School Community Journal, 23(1), 223–244. https://www.schoolcommunitynetwork.org/SCJ.aspx

Grauer, S. (2012a). The costs of schooling: Small schools, entrepreneurship and America. https://smallschoolscoalition.org

Grauer, S. (2012b). The politics of school size. The Grauer School. https://smallschoolscoalition.org

Grauer, S. (2012c). What is a real small school? A review of the literature on absolute secondary school size. The Grauer School. https://smallschoolscoalition.org

Grauer, S. (2015, October 15). Forget football and prom: What big high schools get wrong. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/author/stuart-grauer

Grauer, S. (2023, March 1). Guardrails. The Grauer School. https://www.grauerschool.com/campus-life/stuarts-page

Haller, E. (1992). High school size and student indiscipline: Another aspect of the school consolidation issue? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737014002145

Hamlin, D. & Li, A. (2020). Factors mediating school safety in charter schools: An analysis of five waves of nationally representative data. Journal of School Choice, 15(3), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2020.1783475

Hanson, M. U.S. Public Education Spending Statistics. (2022, June 15) Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/public-education-spending-statistics

Hill, D. (2001, October 1). Breaking up is hard to do up. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/education/breaking-up-is-hard-to-do/2001/10

Hobbs, V. (2003). Distance learning technologies: Giving small schools big capabilities. Rural School and Community Trust.

Howley, C. & Bickel, R. (2000). When it comes to schooling … Small works: School size, poverty, and student achievement. Rural School and Community Trust.

Hu, W. (2012, January 25). City students at small public high schools are more likely to graduate, study says. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/26/education/new-york-city-students-at-small-public-high-schools-are-more-likely-to-graduate-study-finds.html

Husbands, J., & Beese, S. (2001). Review of selected high school reform strategies. Paper presented at The Aspen Program on Education’s Workshop on High School Transformation, Aspen, CO.

Jimerson, L. (2006). The hobbit effect: Why small works in public schools. Rural School and Community Trust.

Kaufmann, W., Borry, E. L., & DeHart-Davis, L. (2018). More than pathological formalization: Understanding organizational structure and red tape. Public Administration Review, 79(2), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12958

Khan, S. (2012, January 20). Reinventing education: The future of learning. Speech presented at the California Association of Independent Schools, San Francisco, CA.

Klonsky, M. (2011, May 11). An interview with Deborah Meier on the small-schools movement. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-klonsky-phd/deborah-meier-small-schools_b_859362.html

Learning Policy Institute. (2017, September 13). What’s the cost of teacher turnover? https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/the-cost-of-teacher-turnover

Lee, V. E., & Loeb, S. (2000). School size in Chicago elementary schools: Effects on teachers’ attitudes and students’ achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312037001003

Letgers, N. E. (1999). Small learning communities meet school-to-work: Whole-school restructuring for urban comprehensive high schools. Center for Research on the Education of Students Placed At Risk.

Levin, H. & Rouse, C. (2012, January 25). The true cost of high school dropouts. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/26/opinion/the-true-cost-of-high-school-dropouts.html

Logan, D., King, J. P., & Fischer-Wright, H. (2008). Tribal leadership: Leveraging natural groups to build a thriving organization. Collins.

Matthews, J. (2014). Web. The Washington Post. America’s most challenging high schools. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/americas-most-challenging-high-schools-2014/2014/04/03/b3f480d2-b8f2-11e3-899e-bb708e3539dd_story.html

McRobbie, J., (2001, October). Are small schools better? School size considerations for safety and learning. WestEd.

Meire, D. (2002). The power of their ideas: Lessons for America from a small school in Harlem. Beacon Press.

Merit, J. L. (2022, Winter). All aboard. Sierra Magazine, 12–13. https://digital.sierramagazine.org/publication/?i=770798&p=1&view=issueViewer

Mitchell, S., (2000). Jack and the Giant School. Institute for Local Self-Reliance. https://ilsr.org/jack-and-giant-school

Murnane, R. J., Reardon, S. F., Mbekeani, P., & Lamb, A. (2018). Who goes to private school? Education Next, 18(4). https://www.educationnext.org/who-goes-private-school-long-term-enrollment-trends-family-income

Nathan, J. & Thao, K. (2007). Smaller, safer, saner successful schools. Center for School Change.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (1998). Violence and discipline problems in U.S. public schools: 1996-97. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs98/98030.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2019). Fast facts: Public and private school comparison. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=55

The New Rules Project. Small schools versus big schools. (2011). http://www.newrules.org/equity/rules/small-schools-vs-big-schools

Nguyen, T. S. T. (2013, March 22). High schools: Size does matter. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/11372322/high-schools-size-does-matter-the-college-of-education-the-

Oxley, D. (2004). Small learning communities: Review of the research. The Laboratory for Student Success at Temple University Center for Research in Human Development and Education.

Oxley, D. (2007). Small learning communities: Implementing and deepening practice. Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

Oxley, D., & Kassissieh, J. (2008). From comprehensive high schools to small learning communities: Accomplishments and challenges. FORUM, 50(2), 199–206. https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/forum

Ramsey, R. (2011, October 27). When letting students slip away looks like a budget blessing. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/28/us/when-school-dropouts-start-to-look-like-a-budget-blessing.html

Raywid, M. A. (1980, November). Restoring school efficiency by giving parents a choice. Educational Leadership, 38(2), 134–137. https://www.ascd.org/el

Raywid, M. & Oshiyama, L. (2000, February). Musing in the wake of Columbine: What can schools do? Phi Delta Kappan, 81(6), 444–449. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/pdk

Richardson, S. (2022, April 6). How China’s authorities aim to control Tibetan reincarnation. https://www.goodreads.com/group/show/152441-book-riot-s-read-harder-challenge

Robertson, F. W. (2007). Economies of scale for large school districts: A national study with local implications. The Social Science Journal, 44(4), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2007.10.005

Rowland, B. (2009, September). Sticks and stones school bullying: What every parent must know. San Diego Magazine. http://www.sandiegomagazine.com/media/San-Diego-Magazine/September-2009/Sticks-and-Stones

Saiz, N. A. (2022). What are student and staff perspectives on the influence of smaller learning communities on sense of belonging and academic achievement [Doctoral dissertation]. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/educ_teelp_etds/360

Simone, A. (2016, December 16). I wish I had a pair of scissors so I could cut out your tongue. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/17/opinion/sunday/i-wish-i-had-a-pair-of-scissors-so-i-could-cut-out-your-tongue.html

Slate, J. R., & Jones, C. H. (2005). Effects of school size: A review of the literature with recommendations. Essays in Education, 13(1). https://openriver.winona.edu/eie/vol13/iss1/12

Stiefel, L., Iatarola, P., Fruchter, N., & Berne, R. (1998). The effects of size of student body on school costs and performance in New York City high schools. Institute for Education and Social Policy.

Thompson, M. G. (n.d.). Nostalgia for high school: rosy memories or thorns? http://michaelthompson-phd.com/2012/04/nostalgia-for-high-school-rosy-memories-or-thorns

Thorkildsen, R., & Scott Stein, M. R. (1998). Is parent involvement related to student achievements? Exploring the evidence. Phi Delta Kappa. https://pdkintl.org

Wasley, P. A., Fine, M. Gladden, M., Holland, N. E., King, S.P., Mosak, E., & Powell, L.C. (2000). Small schools: Great strides. A study of new small schools in Chicago. Bank Street College of Education.

Wasley, P. A. & Lear, R. J. (2001, March). Small schools, real gains. Educational Leadership, 58(6), 22-27. https://www.ascd.org/el

Wilson, V. (2006) Does small really make a difference? An update. A review of the literature on the effects of class size on teaching practice and pupils’ behaviour and attainment. Scottish Executive.

Zane, N. (1994). When “discipline problems” recede: Democracy and intimacy in urban charters. In M. Fine (Ed.), Chartering urban school reform (pp. 122–135). Teachers College Press.

Download this whitepaper:

Subscribe to Small Schools Coalition updates to receive a free PDF version of this research.

Recent Comments