“True teaching is not an accumulation of knowledge, it is an awakening of consciousness which goes through successive stages.”

This article comes to us by way of an publicly anonymous comrade of the Small Schools Coalition, who has an interesting story to tell….

Like many people of my generation (later Gen X’er here), I never had the opportunity to step foot in a small school, or even inside a unique educational environment once I left preschool. After that, and no matter which side of the country I lived on, or what grade I was in K-12, every school I attended and class I took was pretty much the same. The schools themselves were tough, impersonal and at times, flat-out dangerous places. The best I could hope for most of the time was to virtually disappear, because it seemed like whenever I was recognized things never turned out well for me. And that is what I thought was “normal” in terms of education for the first chunk of my life.

In fact, I did not enter what could be considered, in the spirit of the Small Schools Coalition definition of the term, a “Small School,” until I was a graduate student at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona. I will never forget the first Flagstaff Arts and Leadership Academy (FALA). There were only around 300 children in the entire school. That figure was less than the number of students in my high school graduating class by 50%! To see how those children interacted with that teacher, who was more of a guide than authoritarian figure, rocked my world. That was the first time I could begin to wrap my mind around rethinking what education could be.

Let’s spend a little bit of time rethinking what education could be, based on what many people, myself included, grew up being taught was “normal.” Then, let’s take a look at how a few Small Schools Coalition members are helping their students and communities prepare to succeed in our constantly evolving “new normal” that large, traditional schools like mine were never even designed to address…

The One Best System for Education

On more occasions than I can count in the recent past, I have found myself rethinking what education is and could be based on one internally-posed question: What if small schools were normal? Meaning, what if I had grown up in a society that had not abandoned small learning communities over a century ago now, for what Educational Historian David Tyack called “The One Best System?”

Of course, what any of us human beings consider to be normal, and for that matter abnormal, is based on both formal and informal educational processes. Whether learned in school, at home or on the streets, we create and sustain our everyday realities based on what we are taught that reality should be much more so than what it could be.

I lived on both coasts as a child, and a state or two in between. No matter where I lived, the schools I attended, and the classes I took, all bore a striking similarity to each other in form and function: Large and generic. That is not by accident, but rather by design. But where did this design come from?

To understand this, we must venture back to the mid 1800’s. Until that point in American history, schools and their governing boards were ethnically invested in their constituents, and were comprised mainly of neighborhood inhabitants that shared cultural similarities and community interests. This included small local schools based on religious and/or ethnic affiliation that taught children needs more specific to their communities, such as agriculture or basic technological and mechanical skills that would help students meet the needs of their societies’ when they are ready to go to work.

The Centralization of Education in the United States

The influx of immigrants coming from places like Ireland, Eastern Europe and Russia, began to ranckle the Western European Anglo-Saxon Protestant immigrant community for several reasons. First, these immigrants had strange customs and languages. They did not act like the English immigrants. Or, as Educational Historian David Tyack put it, “Perceiving a decline in their social authority and an increase in sin and disorder, Protestants waged a vigorous campaign to inculcate their morality in a society becoming increasingly pluralistic” (Tyack, 1974, Pg. 105).

Second, members of those Western European immigrant cultures were primarily responsible for the proliferation of industrialization in the United States during this time. Immigrants were only viewed as potentially worthwhile if they could be indoctrinated into a capitalist economy. This economy did not value artisans or musicians nearly as much as textile plant workers. Public education was considered to be the most effective means of socializing future workers to “The new modes of production, attuned to hierarchy, affective neutrality, role-specific demands and extrinsic incentives for achievement” (Tyack, 1974, Pg. 73).

Seeing Beyond Liberalism and Conservatism

By the end of the 19th century, a cadre of wealthy businessmen, Protestant clergy members, and influential politicians planned for an education system vesting political power in small committees that would ensure the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon culture. Among other things, they ridiculed the “exceedingly democratic ideal that all men are created equal and urged that schooling be adapted to social stratification” (Tyack, 1974, Pg. 126). These men believed that their cultural and religious upbringing made them favored over other human beings, which allowed them to have wealth and success at the expense of others.

This was called “The Gospel of Wealth.” It was, and still is based on an interpretation of the New Testament that some interpret or translate to mean those with wealth and social prominence are closer to God. Schools were designed to replicate this exclusive heaven on earth, where the people in charge are meant to serve as a bridge between God and the common man.

The Gospel of Wealth is not a liberal or conservative thing, but a Protestant one used by both liberal and conservative influences during this time to justify the divine nature of their plan. In the United States, “liberal” originated as a largely economically deterministic point of view of some Protestant people who believed the bible should be interpreted based on economic principles and specifically, industrial capitalism.

Important to note is that there were no “conservatives” at that time in the United States as they are defined now, because up until that point Protestantism had always been interpreted from a largely religiously deterministic point of view. So, in the Protestant community back then, conservatism was just normal Protestantism. As Professor Eliot Eisner exhaustively documented in his life, this influence directly affected schools.

On one hand, schools are places where lack of individual control reinforces an eventual future where workers will enjoy relatively little if any autonomy. Specifically, principals and administrators are the owners/CEOs, teachers are middle management and students are hourly employees who punch a clock (i.e. ring a bell) to move from station to station during the course of their workday. They learn just enough this way to be able to function on a production line, or in a shop somewhere. This represents the liberal influence behind centralization.

On the other hand, schools are designed to be places where subservience to authority reinforces a present where human life is believed to result from sin. The only way to overcome this sin is to create a covenant with the Protestant-Christian God. Specifically, principals and administrators are God, teachers are clergy and students are parishioners who, it is assumed, are pre-dispositioned to cause trouble because that is their nature. They learn just enough to favor Protestantism as a behavioral code if not religious practice. This represents the conservative influence behind centralization.

Standardized Education Spreads Nationwide

These larger, standardized school systems were in place throughout the United States by the 1930’s. It really did not matter to the people in charge if students in these large, formal schools were Protestant, Jewish, Catholic, Muslim, Hindu or Pagan. It did not even matter if they had learning difficulties that were not obvious enough to keep them institutionalized, like in the cases of people with Down Syndrome and other severe disabilities.

All that really mattered to this cadre of influential people is that children go to school to fulfill the larger economic and social cues every person who is not already benefiting from the gospel is assumed to lack knowledge of. These cues are meant to supersede any individually existent characteristics and behaviors that might otherwise conflict with them (like native languages and rituals). They were canonized in textbooks by scholars like 19th century Professor of History at Columbia University David S. Muzzey. Muzzey believed that Americans, or Us. were people like himself; land owning, genteel Anglo-Saxon Protestant Western Europeans.

To Muzzey, Them were the immigrants, the masses that were causing society to become too pluralistic. Muzzey believed the burden of Americans such as himself was to “Assimilate and mold into citizenship them.” He also felt that failure to assimilate them risked “an undigested and indigestible element in our body politic, and a constant menace to our free institutions” (Fitzgerald, 1979, Pg. 63). By indoctrinating his foreign elements (i.e. human beings), Muzzey and those he represents are able to manufacture a status quo that relies on the health of the established economic and social systems to maintain.

In this context, the entire “melting pot” ideology, historically seen as neutral or equal for all American citizens, is really a metaphor for everyone becoming “Us” in behavior and/or performance. In the process of “becoming,” any behavior, lifestyle, ritual, practice or point of view not considered acceptable to Muzzey et. al was to be buried deep down inside, and kept out of sight at all costs (Pai. Adler and Shadiow, 2006). That is how the “status quo,” or mainstream norm in our industrial society was manufactured.

Education for Maintaining the Status Quo

The status quo being ever-changing, the textbook industry has done its best to keep up with the current discourse and ideology of the time period. According to Frances Fitzgerald, a movement in the early part of the 1900’s through the 1930’s would influence curricula in a liberal way. This included heavily stressing economic individuality and mobility tied to Capitalism as a marker for achievement and equality.

In the 1940’s, things moved toward a more conservative social discourse around the events of WWII, which left curricula stressing the moral seriousness of being an American in a conservative manner. This included a push towards unity against a common enemy and self-sacrifice for the better of the nation. The late 1940’s/early 1950’s brought an even stauncher morally conservative, anti-communist and at times, overtly religious social agenda. This conservatism was supported by liberal representation stressing consumerism to support Capitalist economic and financial institutions in the name of Freedom and Democracy.

The 1960’s and 70’s saw heightened distrust of capitalism and the government, which caused a slight “burp” in curricular delivery where educators, scholars and some parents began challenging the narrative schools had been espousing since the turn of the century. But the 1980’s successfully reasserted materialism, and the 1990’s brought the rigidly standardized No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). This resolidified the status quo (for the time being at least), while also resolidifying the trend began in the 40’s toward passive consumerism as an extension of active patriotism.

This form of economic one-upmanship to display successful societal participation remains prevalent in both schooling and society today. Or, we are taught to strive for success solely by supporting the system the way it is based on what we learn in school, and don’t rock the boat too much otherwise. This warning is silently (or not so silently) lobbed toward individuals across many disciplines, industries and social circles. It also applies to ideas and institutions themselves that challenge widely accepted beliefs… like many of the researchers, administrators, teachers, parents and students in the modern day small schools movement.

How a Small School Benefits Everyone

Despite this, many small schools are successfully merging the history of intimate, community-involved learning (i.e. small schools); with the present day circumstances resulting from 150 years of schools, districts and oversight agencies like the US Department of Education taking schooling in general, and school size in particular, in an entirely different direction.

Whereas the entire idea behind the melting pot was that there is indeed one best way to do things, and everybody should mold their reality to that way, small schools resemble something more like a salad bowl. In a salad bowl, all ingredients (people) retain their distinct individuality or flavor, but come together equally to enhance the overall experience (society).

The success of the following schools and their students testifies to the fact that there is never one best way to do anything in education… at least, not if schooling is going to benefit everyone in their own life-affirming way, instead of just a relative few at the expense of many others.

Take, for example, The Arbor School of Central Florida. The Arbor School provides customized, therapeutic education for children with high functioning Autism, Dyslexia, Down Syndrome, Asperger’s and other Learning Disabilities. Instead of hard desks and cold chairs, Arbor uses fitness balls, bean bags and other sensory-based approaches to provide an environment in which students can learn, grow and thrive.

Like Arbor, the Otto Specht School in Chestnut Ridge, New York provides a variety of educational programs designed to meet the needs of students with developmental delays, social and sensory sensitivities, and learning challenges. They provide developmentally appropriate academic and artistic curricula in small, individualized class settings. Artistic activities including speech and movement. Visual and musical-based methodologies are integral to classroom activities, as are practical skills such as cooking, weaving, wood- and metalworking, farming and animal care.

It is important to note that both Arbor and Otto Specht fill dire needs in our society for children who grow up to be adults with conditions like Down Syndrome. Historically, these children were separated from their peers and families and placed in institutions. Eventually, they were integrated into large schools and the curriculum/structure that already existed was modified slightly for their needs. But that curriculum was not custom designed for them, nor can it ever possibly come close to replicating the success and quality-of-life of a curriculum that is.

How about the Community School in New Hampshire? At the Community School, students in grades 6 -12 and their teachers collaborate in small multidisciplinary classes, at community meetings, and on the school’s farm and forests. The school’s mission is to build a healthy local community that contributes to a sustainable world. Unlike rural country schools’ long gone now, however, the Community School is focused on trying to help get our planet back into better balance because industrial capitalists did not take environmental sustainability into account 150+ years ago.

The Grauer School in Encinitas is also spearheading sustainability on and off campus. Boasting LEED Certified sustainable buildings, farm-to-table agriculture and a handful of other green initiatives, Grauer is at the forefront of the small schools sustainability movement. But Grauer School also specializes in cultural sustainability and preservation. Specifically, its expeditionary learning programs allow students to venture out locally, nationally and globally to interact with the world around them. Expeditions celebrate diversity by respecting each person, group and culture as they are; instead of trying to coerce or force them to adopt Grauer School norms, values or customs for acceptance and equality.

As amazing as all these schools are, there is no more fitting example to drive home the potential of small schools in rethinking the school experience than the Waiahole School located in the Waiahole farming valley on the island of Oahu. The school celebrated its 130th anniversary in September, 2013. As one of the oldest and smallest schools on Oahu, Waiahole School is the heart of the Waiahole-Waikane community.

Not only does it stress academic achievement, Waiahole also places equal importance on cultural preservation and heritage. As a result, students leave 6th grade with not only a solid academic foundation, but just as importantly a solid understanding of what makes them unique and important that is based on other things than prevailing societal cues like material accumulation as markers of successful citizenship.

Put the Spotlight on the Education System

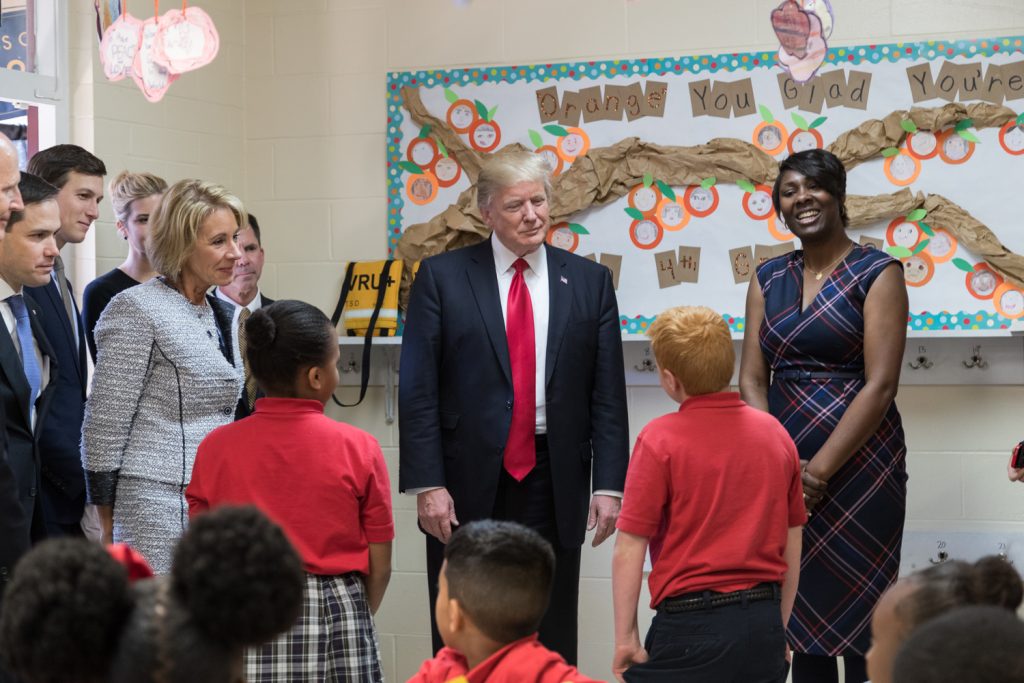

Current Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and President Donald Trump visiting a local D.C. area classroom. Photo Credit: The White House Public Domain Mark 1.0

It is no secret that large mainstream schools, like the elementary, middle and high schools I attended when I was a child were not designed, structurally or curricularly speaking, to provide the kind of student-centered learning experience these small schools do. And this is a problem.

We can point fingers at teachers, students or parents for the failures of mainstream education in recent decades. But the problem is the system itself. It was never designed to accommodate or evolve. While our global society has evolved, and nations continue to overtake us in educational performance relative to modern trends and needs that go beyond production line capitalism, we have made only small surface level changes to a system that was created solely for that purpose.

At the same time, while our society has become even more diverse than it was then, mainstream education is still largely geared toward delivering an experience that teaches students, as Tyack recalls former New York City educator Leonardo Covello putting it, that “Italian (or Irish, or Jewish, or African, or Hispanic, or disabled, etc.) meant inferior.” Anything more than surface level changes to the original curricular structure or content are still not tolerated at this point… at least not at the mainstream level.

And that is why small schools are so vitally important. The schools above are just a brief glimpse of the schools that should be celebrated for doing their own thing to the benefit of their students and communities. Personally, I have learned to celebrate them whether or not the school’s curriculum is aligned with my personal, private beliefs and goals. I celebrate them all equally regardless, because their shared passion for intimate, student-centered learning supersedes any differences in their missions and values. Can you imagine what our nation would look like populated with thousands upon thousands of small schools that serve and celebrate their native, local and national communities and cultures at the same time?

Meet the New Boss…

Okay, so the past 150 years have bestowed upon us a nation of large, cold institutional campuses that can just as easily be confused for prisons as schools in many cases. This refers to both the architecture and curriculum. Like many other people, I was an inmate at those institutions. I did not have a choice other than to play hookey, which I admittedly did quite a bit.

So I know firsthand that subjects like ‘readin’, writin’ and ‘rithmetic are standard no matter when, where or what…. while subjects like music, the arts and even physical activity and exploration are treated as fringe benefits at most. And it is these pursuits that help us truly define ourselves as truly alive human beings, not merely living functions of profitability.

It is obvious that if small schools like these are going to work on a large scale, people need to work together on grassroots-community levels in most if not all cases, versus trusting the interests of those in power to guide their educational destinies. This concern refers directly to privatization of education based on the shortcomings of the current education system.

Privatization is an ongoing bipartisan effort. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is attempting to do this under President Donald Trump, and previous secretaries including Arnie Duncan (liberal Democrat) and Rod Paige (conservative Republican) have attempted to do for presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush respectively. In fact, privatization attempts over the past 30 years are nothing more than a governmental backlash to diversity from all sides.

This is why, under current circumstances, government-promoted privatization and efforts to use federal dollars as a way of influencing departments of education will make things worse—and they will not promote what’s best about small schools, public or private. It will continue to primarily only financially and socially benefit relatively few already wealthy people like the DeVos family, and those (like politicians) their wealth influences.

This is actually a huge part of the problem with privatization in general, in that it simply allows those who already have control over societal processes to regain and/or gain more of it without direct competition. Of course, these people also maintain very strong motivations to ensure curricula maintains existing control individually and/or culturally speaking.

Nowhere is this seen more clearly currently than in Arizona. For the past several years, charter school budget money is being used to heavily pad the pockets of state lawmakers who own the companies that run private charter schools for profit. And just like DeVos is attempting to do on the federal level, some of Arizona’s money is also going to schools that discriminate toward people who do not look, act and think like Muzzey and his friends.

Meet the new boss, same as the old, right? Unfortunately, for every upstanding small charter school like FALA, more and more investigative research indicates Arizona, and many other states like it, has exponentially more compromised ones like Benjamin Franklin Charter Schools.

Pondering the Future of Small Schools in our Large World

Is mainstream education nationwide locked in this large, general, relatively narrow trip for the rest of eternity? There really is no easy answer here. Do true Small Schools work? The ever-growing body of “real-world” research indicates yes the definitely do. The anecdotal evidence from scores of parents, students and community members supports this research.

Could they work on a larger, more inclusive scale? Yes, they could. But, would it be easy to rethink the educational experience from the ground up at this point on a large scale, and whether or not that begins on the grassroots or governmental levels? No, and only a fool would assume otherwise.

Barring an educational revolution, which has successfully occurred at least once in the past century just as point-of-fact, those of us who have been positively affected by small learning communities have the responsibility to make sure small schools continue to be represented in both the educational arena and curricular discussion. As organizations like the Small Schools Coalition continue to grow in membership, coordination and influence, who knows how far small learning communities can venture toward the mainstream middle?!

I was already beginning to understand that on some academic levels before that day at FALA. But what I saw in that classroom, which was much more like a community rec center than any history class I ever sat in when I was a kid, shocked me to my core. That might have been the first time I was actually educated about anything in a K-12 classroom in my entire life. Not taught something to memorize without thinking critically about it. No, I was actually able to teach something to myself. This helped me reconcile how I saw the world until then with how I then saw the world could actually be from then on.

Needless to say, that shock is all it took for me to begin rethinking education for myself. My hope is that there are many others, regardless of their cultural background, political affiliation, religious upbringing, or societal authority, who are willing to experience a little shock themselves… and in the process, realize that “normal” does not have to be what came before; especially if that was based more on the best interests of the few than the many children and communities education should serve locally, nationally and globally speaking.

If you would like to discuss the power and potential of small schools for rethinking the educational experience for students and communities everywhere, or to inquire about a complimentary membership to the Small Schools Coalition, we welcome you to contact us!

References

In addition to any in-content links to other reference materials/articles on and off-site, the following material was either directly quoted, or factual content in this article came from direct knowledge of information contained in these sources. For more specific citiation information, please contact us directly….

- Adler, S., Pai, Y., Shadiow, L. Cultural Foundations of Education. Pearson. NJ, 2006

- Apple, M. Educating the “Right” Way: Markets, Standards, God, and Inequality. 2nd edition. Routledge. NY, 2006

- Apple, M., Christian-Smith, L. The Politics of the Textbook. Routledge. NY, 1991

- Berliner, D., Biddle, D. The Manufactured Crisis: Myths, Fraud and the Attack on America’s Public Schools. Basic Books. NY, 1996

- Eisner, E. Educational Imagination. Macmillan Publishing Company. NY, 1979

- Fitzgerald, F. America Revisited. Little Brown & Company. MA, 1979

- Friere, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum. NY, 1993

- Giroux, H. Ideology, Culture and the Process of Schooling. Temple University Press. PA, 1983

- Green, J. The World of the Worker. McGraw-Hill. NY, 1980

- Tyack, D. The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education. Harvard University Press. MA, 1974

Recent Comments