“When we experience nature’s amazing beauty,

we feel in awe of its healing benefits.”

As 2019 draws to a close, we at the Small Schools Coalition remain most grateful for our faculty, members, friends, supporters. We are also grateful for everyone who is passionate about the myriad benefits small learning communities have in the lives of students, educators, families… and ultimately, the larger societal communities served by each and every one of them.

During the holiday season, we ask everyone to remember and pay respect to the fact that there are indeed some issues that transcend small schools versus large schools; independent schools versus public schools; and every other institutional nuance contained within the vast educational landscape.

Foremost among these issues is the effect of climate change on children. Of course, many communities and schools are already focusing attention toward the ecological/environmental effects of climate change. But very few at this time, both large and small, have the curricular framework in place to address the psychological, behavioral, and overall inner health-wellness effects of climate change on children.

It is to this urgently important topic that we dedicate our last blog article of 2019. This article is a reprint of the speech our Founder, Dr. Stuart Grauer, presented at the OESIS Conference on Student Wellness in Los Angeles, California on October 31, 2019.

As you read this, please keep an open mind as to how you -as an educator, administrator, parent, student, or just concerned member of our human community, hold the key to helping mitigate the effects of climate change on children… and what you can do to make the most of your platform!

I. Introduction

Good morning and welcome to the OESIS Student Wellness conference and gathering.

My name is Stuart Grauer. I am the founder of several schools including, since 1991, The Grauer School, and I am also coming out today as the thief of childhood.

The Grauer School is in Encinitas, California, and we are fairly unique among college prep schools in that we grade not only tests and quizzes, but equally the achievement of values like engagement and courage. We encourage activism. In nationwide surveys of student engagement, our students have consistently ranked in the 99th percentile in health-related areas such as connectedness, belongingness, engagement, and sense of safety. While developing our school, I dedicated 40% of our campus to a wildlife and native habitat corridor, and every class spends substantial time outdoors. Our Access to Grauer endowment discounts hundreds of thousands of tuition dollars each year so we can include deserving kids of diverse backgrounds. All of these provide a connection to health and wellness I hope you will see by the end of this talk.

Working with teens every day for four-plus decades I have seen pain and troubles, agonies and ecstasies of all kinds, some deep and painful, many joyful. Two books of mine (Real Teachers and Fearless Teaching) have been published, telling stories about some of the painful, joyful lessons teachers are learning around the world, and I have brought some to give away to people who want them after this talk. I have just returned from the Andes Mountains with my students, studying with indigenous Yakchaks or shamans, which has further informed my thoughts on this topic.

II. The Trouble for Educators

These days, I have been troubled by some of the toughest decision-making in my life as an educator of teens. Working with teens poses a never-ending assortment of challenges, but new dilemmas are moving up to the top of my list.

News that our local and global ecosystems are at grave risk is hard to escape. Facts like this: many scientists predict that by 2050, the volume of plastic in our oceans will equal the volume of animal life in the ocean. According to NOAA, microplastics, small plastic pieces harmful to our aquatic life have filled in gigantic sinks in the sea and we have no idea what impact this will have on life—and this is set to triple in the next 10 years (UN Global Environment Programme, 2018). The debates about environmental disasters just keep queuing up, but this is not the specific issue that has troubled me and brought me here today.

A consensus of scientists whose findings you can only disregard if you play ostrich, are predicting that by the end of the century, 50% of the world’s species may be extinct. According to a new study in the journal Science that scientists call “staggering” and some others call part of a socialist scheme to undermine western civilization, we have a net loss of almost 3 billion breeding birds in the U.S. and Canada since 1970 (Rosenberg, K., Dokter, A., Blancher, P., Sauer, J., Smith, A., Smith, P., Stanton, J., Panjabi, A., Helft, L., Parr, M., & Marra, P., 2019).

Worse still, we as teachers have mostly sat around and watched this happen and done little or nothing, myself included. It feels like habitat loss, pollution, and overpopulation are like TV shows we are passively watching from rooms where we sit. And teens today are spending more time in their rooms and not outdoors than at any time in history, as though they are hiding, as entertainment becomes the province of the digital screen and the chair. But, no, those are not the big troubles I am bringing to you today as a teacher.

The trouble, the real trouble I have today, stems from the fact that I have always treated my role as an educator as value-free: the teachers create engaging environments and the teachers provide the sanctioned curriculum materials. It’s the SOP. Some of that worked for me for many years because I always felt that students need space to grow up, politics free, without our agendas, in their own time. So, the trouble is that I am aware of all these looming, undeniable debates about where our planet is heading, and I wonder how I can abide by the passive, nonjudgmental role as an educator. I wonder how much longer I can ignore the overwhelming findings of climate chaos, go about my merry classroom business as usual, or pretend all this noise can be written off as in the purview of toxic political squabbles far from the ivory tower, separate from the classroom where my students are safe and sound.

I have been struggling with the prospect of weighing my students down with heavy, heavy global issues, the extracurricular matters for existential despair. They’re kids! I want them to have an innocent childhood. I want them to shag fly balls in sunny, slow time, and to have hopeless crushes. I don’t want to hit them with the threat of devastated biomes, the extinctions, the hundreds of millions of refugees fleeing uninhabitable lands presided over by desperate governments we may see in the coming decades, threats which my generation and those around it helped bring about and have not yet done much about.

And so, my real trouble is not climate change, it is that I don’t want to steal childhood from my students. I don’t want to be the thief of childhood. These are devastating findings coming in almost daily like body blows to the spirits of innocent, trusting children, and based upon enough scientific consensus to heed, and I have stood on the sidelines, watching it happen, delivering the curriculum.

III. The Mental Impact of Climate Change

What are the risks of the passive, business as usual behavior many of us are taking? The US Global Change Research Program (2016) notes that if a climate crisis escalates, we could anticipate various mental health impacts such as these three:

- There are mental health consequences for people who experience extreme weather events, such as PTSD, depression, general anxiety, substance abuse, suicidal thoughts, grief.

- The threat of extreme weather events can also be a stressor. Over 50% of Americans report being worried about climate change.

- The hybrid of natural and human causes of climate change can result in feelings of heightened risk perceptions, preoccupation, general anxiety, pessimism, helplessness, eroded sense of self and control, stress, distress, sadness, loss and guilt.

In 2017, the American Psychological Association reported these long-term climate change effects on mental health: loss of personal and professional identity; loss of social support and structures; loss of sense of control, autonomy, helplessness, fear, fatalism (Clayton, S., Manning, D., Krygsman, K., & Speiser, M., 2017). The APA even termed “climate-related despair” as a distinct mental health condition because climate change can cause people intense stress and anxiety (Woodward, B., 2019). It could have a sweeping impact on daily life. Students who are struggling emotionally already may feel helpless due to the effects of climate change.

Recent studies indicate a significant increase in suicides related directly to temperature increases as well as long-term negative impacts on cognitive functioning from exposure to air pollution. Higher rates of individual and group violence have also been associated with increases in temperature. Many clinicians are reporting that their patients are worried about the future of geophysical and political environments—our sense of place under siege. We are seeing myriad social, cultural, and health consequences of mass migration stimulated largely by global environmental disruption, and those will get worse (Pollack, D., 2019). The effects of increasing global temperatures, rising sea levels, excessive CO2 levels, droughts, and other extreme weather events, reflected most recently by the spate of historic hurricanes, cyclones and wildfires, combine to threaten the health, well-being, and economic stability of individuals, communities, and nations worldwide.

There is science and stakes on all sides of the climate change issue, so the issue has become just as political as it is ecological. Recently, I expressed this concern to a strong climate change skeptic. I cited data from the World Health Organization about the impacts of this whole issue on children, and not on the climate science. He responded that I was a liberal on “an illiterate rant” (personal communication with Bud Bromley, October 10, 2019). Even for many children whose homes are sheltered from significant climate change impacts, just the polemics surrounding these viewpoints produces a toxicity that infiltrates the lives of virtually all of our kids—as talking heads slug it out, our children become the victims.

IV. What is the Impact on Young Minds and Spirits?

Jonathan Franze threatened in the New Yorker in September of 2019, if you’re under thirty, “you’re all but guaranteed to witness the radical destabilization of life on earth—massive crop failures, apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, epic flooding….”

The US Global Change Research Program (2016) also notes that children are the most at-risk population:

- Children are at particular risk for distress, anxiety, and other mental health effects, such as depression, clinginess, aggressiveness and social withdrawal.

- More children than adults show prolonged PTSD symptoms after a disaster.

- Chronic stress can alter biological stress response systems and make growing children more at risk for developing health conditions later on (i.e., anxiety, depression).

- In children, stress from climate impacts can cause changes in behavior, development, memory, executive function, decision-making, and scholastic achievement.

My own takeaway is that, after all, maybe I am not the thief of childhood. Maybe we all are: our investors, our corporations, our president, all of us who purchase tropical oils and single use plastics, all thieves of childhood. Anyone who watches from the sidelines, doesn’t read the labels, and does not encourage action is a thief of childhood.

The Psychiatric Times notes there is not much literature on youths yet, but this is a breaking field (Pollack, 2018). David Pollack writes, “The mental health consequences are also vast, pervasive, and likely to last longer than most other impacts on health. They require attention, understanding, education, and commitment … to effectively identify, treat, and prevent” (p. 1).

The iron law of climate change is, the less you did to cause it, the more you feel its effects. Some of that injustice is intergenerational: those who poured the most carbon into the air may be dead before its effects are fully felt. That’s why the leadership of this movement looks the way it does: people from frontline communities, indigenous people, and the young people we teach in our schools today who are walking out of class on strike or claiming they will never have children.

For millions of invisible indigenous peoples whose native lands are lost, who labor on barren remains of rainforests, the modern manifestations of colonization, sense of kith is a myth. And for their children, half a billion of them, who will have no schooling, laboring in factories producing cheap, disposable synthetics, two steps from the landfill before they even hit the bargain stores, childhood is just a forgotten dream (Terre des Hommes, 2017).

According to Gray (2011), young people feel less in control of their lives now than in any other point in recent history. The Internal-External Locus of Control Scale measures this perception. Developed by psychologist Julien Rotter in the 1950s, the scale determines whether people believe they mostly control what happens to them in life (internal locus of control) or whether it is external forces (external locus of control). Between 1960 to 2002, children and college students were increasingly likely to believe in an external locus of control—they feel they are losing their agency (Twenge & Zhang, 2004).

In a 2018 report by the American Psychological Association, nearly half of the teenagers surveyed said they were more worried than they were the year before. A 2013 report by the Yale College Council found that more than half of undergraduates sought mental health care from the university during their time there.

IV. The Action Plan for Educators

Given the grave risks, I wondered long and hard about how much of the truth about the possible devastation we can weigh my own students down with, and this became my research question. I have been looking into the eyes of my high school students and wondering how much can they handle? There’s already a well-documented anxiety epidemic.

Some of our children both here in the “west” and in other “worlds” aren’t afraid to express powerful emotions such as anger, frustration, and grief; and I want to consider a new research hypothesis: Is it through the exploration and acceptance of their wilder emotions that children will come to thrive?

Anjali B is a grade 9 student at The Grauer School and here is what she told me: “What worries me about the future is the condition of the environment and planet, the animals and natural creations. I get deep anxiety and will spend time crying in my room because I’m scared for the planet.”

News of climate change right now is permeating for kids, like a subliminal tape purring through our pillow all night long as we sleep. Even among students who do not read the news, the messaging is ubiquitous, spooling into their subconsciousness, an inescapable subtext in conversations, music, the written word, and all over the world, from urban industrial centers to the suburban beach cities of California to the indigenous in Altiplano where I traveled with my students. All week, high in the Andes of Ecuador, the Quechua patiently taught us. To the indigenous, native plants are medicine, only a fool would damage or replace them—but of course, this has happened on a scale our ancestors could never have dreamed of. At high altitude in the elements, I witnessed my own high school students immerse into the reality of a vanishing world. I witnessed a vulnerability I had never before fathomed. I witnessed catharsis like I had never seen in my classes, pain and fear taking manageable form for the first time as it sought expression. And I witnessed a lightness and an openness emerge in them following this experience. And I now know what to tell Anjali.

Since they stand to lose the most from our action or inaction on climate change, it is to the indigenous and to the youth we owe the truth. Just a few days before we arrived, the voice of the 17-year-old Helena Gualinga reached out from the Ecuadorian Amazon where she is confronting recent fires and increasing deforestation. Her work focuses on advocacy for indigenous people and youths. “By protecting indigenous peoples’ rights, we protect billions of acres of land from exploitation,” she posted on Instagram, where she has 7000 followers. “I grew up with a constant fear that when I would go home my community wouldn’t exist anymore,” she said, answering fear with action.

The reality of climate change can be debated to kingdom come, but the impact it is having on our youths is undeniable, immediate, and in some cases catastrophic. This impact is being felt throughout the world. Where did I get the idea that I could keep it out of the curriculum, unburdening it? It is time: it is time for student activists and artists to be empowered, for action to be welcomed as a fundamental aspect of coming of age and preparing to lead in the next generation.

I asked our faculty about this, and every one of them agreed it was a time for the truth, and for student empowerment.

And I asked a junior class student about this, that is, were we going to steal her childhood, weigh her down. Could her generation handle this?

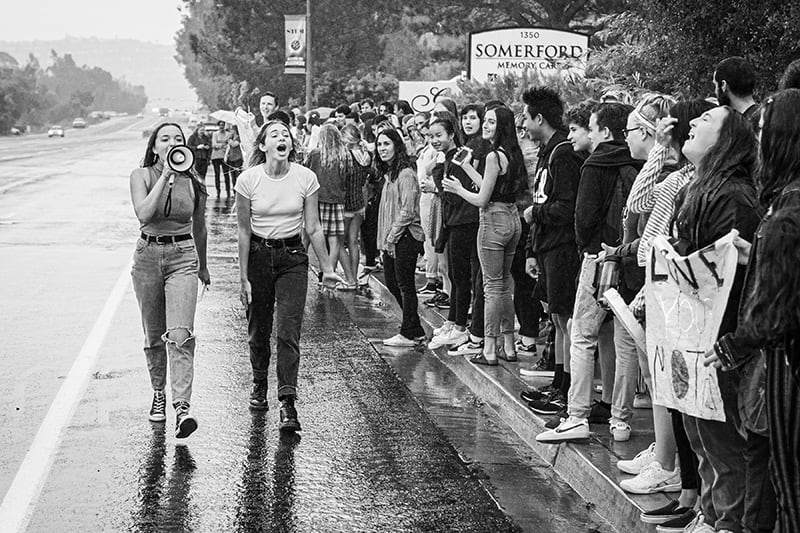

She looked in my eye and said, easy as cake, “Yes. Sure.” I should not have been surprised. These are the same students who took to the streets in the aftermath of the Parkland shootings to advocate for their right to be safe against gun violence in their schools. These are the students who will awaken to the reality of their victimization and only through this awakening, not be anxious and depressed. One teacher said to me: “This is all surrounding them. They need to feel there is something they can do about all this, and not feel helpless.” We are surrounded by wisdom of youths and will not succeed without it.

What can we do to help teens facing these health risks? Psychologists are now telling us that people who have higher perceived environmental self-efficacy are more motivated to act on climate solutions.

Psychological research by The US Global Change Research Program (2016) reveals two points:

- People who are actively involved in climate change adaptation or mitigation actions experience health and well-being benefits

- Engagement addresses both the threat itself and helps manage people’s emotional responses

In other words, when children have a sense of being able to positively engage in climate and/or political solutions, they are more likely to curb anxiety, stress, and other mental illnesses. Dr. Lise Van Susteren, a psychiatrist and founder of the Climate Psychiatry Alliance says taking action can be an empowering antidote to fear. Collective action has mental health benefits.

The time for action is here. This summer of 2019, I took my troubles to our School Board of Trustees, and in a far-sighted governance move, every one of them agreed it was a time for action—we passed a joint faculty-Board of Trustees Climate Change Resolution.

At Grauer, in all courses of study, we are finding study and internship opportunities focused around the environment, sustainability, farming and conservation: Solana Center for Environmental Innovation, Nature Collective, Coastal Roots Farm, and Farm Lab are a handful of them. We now have a student officer for sustainability and increasing student activism that we encourage as students stand up to today’s crazy political landscape. At The Grauer School, as is custom, students petitioned the administration for a climate walk out event, rather than just walking out. But the student leader Thalia M., a junior, informed me, “We’re going to do it whether the petition passes or not.” Right on. Another Grauer student testified before City Hall. Bring it!

As a teacher of teens, watching as the current epidemic of depression has evolved, I know what depression means: it means “I have no control over my life.” It means “my life is not mine to control.” It means victimization. The only way out is empowerment and the highest form of education: taking action. The way out of all this is student voice.

I know the curriculum in almost every college preparatory course is already impacted and should take a year and a half to cover half-well. Broad and evidence-based sets of curricula are essential for all levels of efficacious schooling. The kids easily understand the connections between the climate change issue and health or how can they learn about it. Data show that climate and health related arguments motivate positive action (Pollack, 2018).

Saying I have no space in the curriculum to cover compelling truths with our students is no different than our school’s investment broker who tried to claim that we must not shift our investment to social and environmentally conscious funds because it is the policy of his firm to maximize profit. Time and money are the thieves of childhood.

Eco-anxiety and eco-grief will be growing diagnoses, whether you like the terms or not. Anxiety and depression correlate with a person’s feeling of not having control over his or her life. People with eco-anxiety will watch the impacts of climate change, and experience perceptions of loss, helplessness, and frustration if they feel they can’t make any difference.

Building resilience and agency are the keys, and that is the responsibility of every teacher and school and schoolboard member and curriculum designer in the country. It is time for every real teacher to:

- Build belief in resilience and perseverance.

- Cultivate active coping and self-regulation skills as a part of the curriculum.

- Maintain practices that promote sense of place—there is no truer essence for teaching and schooling than creating a strong, unique culture and sense of community and ecosystem in and out of class.

- Understand our new role in nurturing and teaching activism as a basic skill.

My student, Anjali B., says, “I hope everyone does their part soon … I try to be conscious of decisions that can affect the planet, like conserving energy.”

What Anjali seems to intuitively sense is that her hopes are a direct benefit to mental health. Research shows:

- Physical commuting (biking, walking) enhances sense of well-being. Adolescents who physically commute have lower levels of perceived stress, increased cardiovascular fitness, improved cognitive performance, and higher academic achievement.

- Public transportation leads to community cohesion. Less driving and more exercise leads to reduced stress and depression.

- Just being in green spaces diminishes stress.

- Clean energy reduces health burdens. Children exposed to higher levels of pollution show more attention problems, anxiety and depression, and lower academic performance and brain function.

It is time to get out of the chair—we’ve all heard of sitting disease—time to recast mandatory schooling apart from incarceration, as it seems to many youths some days. A growing body of research shows that people who spend time outside in sunny, green and natural spaces tend to be happier and healthier than those who don’t. A 2015 study from Stanford, for example, found that young adults who walked for an hour through parkland were less anxious afterward and performed better on a test of working memory than if they had strolled along a busy street (Bratman, G., Daily, G., Levy, B., & Gross, J., 2015). Even posters and videos of nature have this impact (van den Berg, M. Maas, J., Muller, R., Braun, A., Kaandorp, W., van Lien, R., van Poppel, M., Mechelen,W., van den Berg, A., 2015). At Grauer, we are live-streaming natural environments daily in various indoor locations around campus.

The awakening for me, as a teacher, is that climate is not the issue. The issue is to empower students in reclaiming the connection and sensitivity to the environment that development, technology, urbanization, and politics have stolen from childhood. The issue is creating spaces where our children and students can take action, express passion and artistry, and be heard with civility.

The great climate strikes that are taking place around the world have roots in the efforts of junior high and high school students who are insisting not only on climate action, but upon their own efficacy, their own sense of empowerment and agency, and their own mental health. Our children and future generations depend on us to act meaningfully and that means teaching them honestly and fearlessly, and listening a whole lot more deeply, understanding that our authentic connection will be basic to healthy schools and communities.

Today’s and tomorrow’s healthiest students will be those who are deeply aware, in a truly hopeful way, of the connections between people around the planet. Even if they can’t grasp the maelstrom of science now being generated, they will understand the stakes, and this is the understanding that will draw them together in action.

Students around the world are watching and responding to one another’s calls to action. They are communicating and connecting with each other, in spite of society’s perceptions of their age and inexperience, perhaps because of it. And now, for the first time since the colonial days, there is no first or third world on an issue: we all share the planetary alert. In my imagination and perhaps soon in real life, Thalia from our beach town school and Helena from the Andes are working hand and hand. Both are coming to see the hidden links between indigenous rights, US teen shopping, and the air they both breathe. Wellness for them both means they will not succumb to the allures and pressures of consumption and profit, but will be driven by a more worthy, shared purpose. This is mental health. This is the magic connection.

Thank the heavens for that—those kids will be less prone to the dark or mentally ill sides of environmentalism, most likely to protect the places they love and to make them inclusive.

For many years, I’ve been taking students on survival trips and ecological immersions, where they sleep under the stars or in rural villages, sometimes at the guidance of locals or indigenous who have everything at stake. I’ve gone through hunting licensing classes with my high school students, and set out into the hills bow-hunting with them—not normal prep school behaviors, and swum with whale sharks with them. Out there in our at-risk earth, everything the experts are telling us about what our kids will need in the coming world is obvious and manifest: a mindset ready for adversity and adaptation; an ethos of self-care; a sense of ecology; a spirit of connection with others and the larger world. What we can see in those connected times in nature is why the enormous sacrifices necessary to overcome our addictions to plastic, energy production, fast foods, sweatshop clothing, ego, and the taking of pristine natural spaces are worth it.

The thief of childhood is not the one who shields the truth from children but rather deprives them of the voice and passion they need to take charge of their lives or of their connection with the natural world. Nothing is more central to every major spiritual tradition than the simple concept that everything is connected, every child is part of a biosphere—this is sustainable health. The teen spirit comes alive in nature and arts, the human mind-spirit-body separateness dissolves, and in those times and places, it is easy for them to see why we all matter.

Fight the Impact of Climate Change on Students Together!

Regardless of our nationalities, customs, races, religions; the amount of money we have in the bank, or anything else that we might let divide us as a species, we are all bonded by the earth we share. We are all bound by our desires for a better world for our children… and to see them grow into healthy and happy adults, with lives all their own. For this reason alone, we owe it to ourselves and them to band together to fight the impact of climate change on students regardless of what type of school they attend or where they live.

If you would like to discuss the impact of climate change on students with Dr. Grauer personally, please contact us and we will gladly put him in touch with you. If you would like to learn more about membership in the Small Schools Coalition, please click here. And from all of us to you and yours, thank you helping make 2019 a banner year for the Small Schools Coalition… and let’s work together to make 2020 and beyond even better for all of us!

References

[1] American Psychological Association (2018). Stress in America, Generation Z.

[2] Bratman, G., Daily, G., Levy, B., & Gross, J. (2015). The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. ScienceDirect, 138, 41-50.

[3] Clayton, S., Manning, D., Krygsman, K., & Speiser, M. (2017). Mental health and our changing climate: Impacts, implications, and guidance. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica.

[4] Dodgen, D., Donato, D., Kelly, N., La Greca, A., Morganstein, J., Reser, J., Ruzek, J., Schweitzer, S., Shimamoto, M., Tart, K., & Ursano, R. (2016). Chapter 8: Mental health and well-being. In The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. Washington, DC, 217-246. Doi:10.7930/JOTX3C9H

[5] Franzen, J. (2019, September 8). What if we stopped pretending? The climate apocalypse is coming. To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent it. The New Yorker.

[6] Gray, P. (2011). The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Play, 3, 443-463.

[7] Magdalena M.H.E. van den Berg, Jolanda Maas, Rianne Muller, Anoek Braun, Wendy Kaandorp, René van Lien, Mireille N.M. van Poppel, Willem van Mechelen, and Agnes E. van den Berg (2015 December 12). Autonomic Nervous System Responses to Viewing Green and Built Settings: Differentiating Between Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Activity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (12): 15860–15874.

[8] Pollack, D. (2019, September). Could climate change cause depression?

[9] Pollack, D. (2018, October 12). Climate change and its impacts on mental health. Psychiatric Times.

[10] Rosenberg, K., Dokter, A., Blancher, P., Sauer, J., Smith, A., Smith, P., Stanton, J., Panjabi, A., Helft, L., Parr, M., & Marra, P. (2019, October). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science, 366, 120-124. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw1313.

[11] Terre des Hommes Child Labour Report (2017). The neglected link : Effects of climate change and environmental degradation on child labour.

[12] Twenge, J., & Zhang, L. (2004). It’s beyond my control: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of increasing externality in locus of control, 1960-2002. Personality and Social Pyschology Review, 8, 308-319. Doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_5.

[13] United Nations Environment Programme. (2018). Legal limits on single-use plastics and microplastics: A global review of national laws and regulations.

[14] Woodward, B. (2019, March 26). Climate disruption and the psychiatric patient. Psychiatric Times, 36.

[15] Yale College Council Report of Mental Health (2013).

Recent Comments