“There’s a gentle mystery to paddling this long river north, as if its quiet currents hide a secret soul below.”

I do not know exactly why I accepted an offer to paddle canoes into the far north country and into the Arctic, but as soon as I got the offer, I knew it felt surprisingly deep seated and connected to something basic to my nature as a teacher or, if you will, my spirit. Or were there just discoveries to be made up there?

Switching planes in Seattle, we boarded a small, regional, twin prop and proceeded to the Northwest Territories of Canada at Yellowknife, a bit of the Old West.

The town of Yellowknife was established in the 1930’s following the discovery of gold in the area. I flew up there on the way to the Arctic Circle for a wilderness expedition with Grauer School alumni dad and technology trailblazer, Kevin Wirick. On that twin prop, I sat near a gentleman with a hat that drew my instant attention. With a native insignia, it read: “Every Child Matters.” Underneath that cap turned out to be Deneze Nakehk’o, who said his name was “Dean.” (I have the full spelling only because I vetted him later). He told me about Yellowknife and gave me good instructions on how to interact with a grizzly.

The city’s name is derived from the Yellowknife Dene First Nation, who were known for their copper-bladed knives. The original gold rush attracted prospectors and miners, leading to the rapid development of the town. Over time, Yellowknife evolved from a native settlement, to a gold mining town, to a small and modern city. This changed the power dynamics of the town, as in towns all over Canada and the U.S., and childhood up there would never be the same for the Indigenous.

Later on, Deneze (Dean) happened by the Yellowknife market where we were lunching and provisioning. I did not know why, but I felt a kinship with Dean and knew I would never forget him. I said that’s a cool hat, what’s the story, and he immediately took it off and handed it to me. I gave him mine, and he told me of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The TRC’s final report, of which he was a contributor, was released in 2015, and documented the deaths of at least 4,100 children in residential schools, although the true number is likely higher. The report called for the identification and protection of residential school cemeteries.

“These colonizers, they knew to take away our power through the women and the kids,” says Dean. He is of the native Dene tribe, originally from Fort Simpson, Northwest Territories, and is related to the Antoine family — he has adopted a native name he considers to be more authentic and not French in origin. Growing up, families like his faced discrimination and racism and many among them grew ashamed to be Dene. Being white seemed a whole lot easier. But Dean overcame that phase with the help of his family and now, uncovering his true family name made him proud and drawn to the Truth and Reconciliation movement, following a horrific chapter in the history of schools up there.

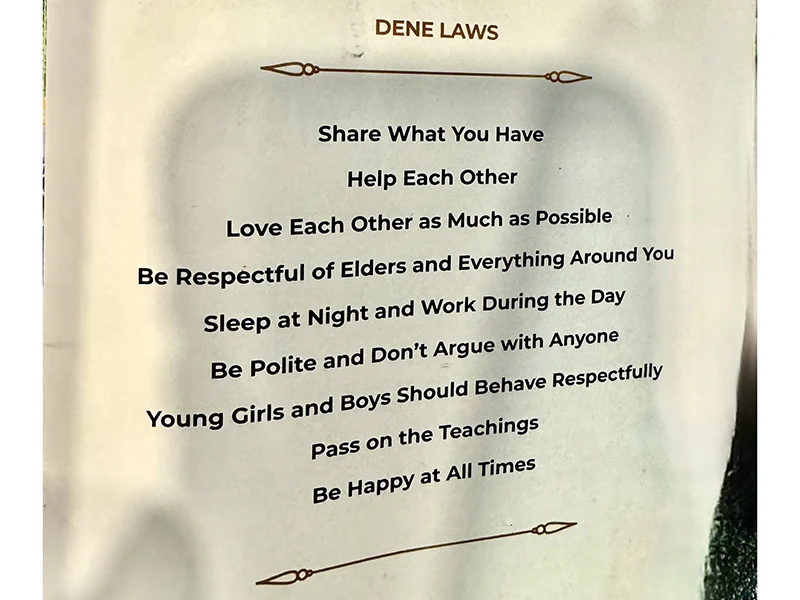

From the market, our expedition group of 8 had a couple of extra days before our long paddle deep into the Arctic would begin, so we continued on our way to Peterson Creek Park. We passed range buffalo and snapped some great photos of a pair of Sandhill cranes and a bald eagle. Nestled a few minutes from downtown Yellowknife, the creek park is a vibrant natural oasis featuring a 4 km trail that led us through lush forests, open meadows, and rugged canyon terrain, with scenic views and abundant wildlife. A payoff of the hike is the stunning Lady Evelyn Falls, where, on a mostly sunny day, the rushing water created a mesmerizing atmosphere — a perfect spot for an invigorating hike. But more than the creatures, it was a man-made sign that got my attention the most, and it bore the number “215”.

Back in Yellowknife, I started reaching for local newspapers and talking to people in the café. The City Council had previously updated the Reconciliation Action Plan in April of this year. Previously, in April 2022, it had been released for public review and engagement on how Yellowknife can collectively advance “reconciliation.” I was learning that the Reconciliation Action Plan has become a living document that can be amended and added to at any time, and is reviewed annually.

Over 24% of Yellowknife’s population is Indigenous, and as the capital of the Northwest Territories, this city is a crossroads for many Indigenous persons coming from different parts of the NWT and beyond. The city government hopes that residents will join in reconciliation events to participate in the tough conversations that lay upstream. Indian boarding schools, also known as residential schools, in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, were part of the larger Canadian residential school system designed to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture.

By the late 1960’s, the residential school system had become ubiquitous in wiping out native culture and it began to face increasing scrutiny and criticism for its treatment of the children. (A similar thing happened in the historic culture of fur trapping and the fur trade, which had sustained the tribal people for many generations, until that industry faced the scrutiny and criticism that nearly killed it.) The last Indian school, Akaitcho Hall, closed in 1996. The closure of residential schools across Canada led to a reckoning with their legacy, including the trauma and lasting impact on Indigenous communities. Maybe I’m old, but 1996 sounds stunningly recent to be enforcing a program of removing children from families for “re-education” into the white ways of life.

I have a deep concern about re-education both as a teacher of 50 years and as the grandson of an Austro-Hungarian who was driven out of his homeland as a young boy in the Russian-backed pogroms, just as the childhoods of many thousands of First Nations children were being taken for many of those years. It is striking that both programs began around the same time, the late 1800s. All of that, and Dean’s hat: “Every Child Matters.”

In studying both the Austro-Hungarian pogroms and the reconciliation efforts in Yellowknife, education can now play a crucial role in addressing historical injustices/atrocities and fostering healing. You can’t look at histories like those and not see that a decent education has to include some activism.

In the Austro-Hungarian context, education back in the homeland was used to perpetuate systemic oppression and anti-Semitic attitudes. Conversely, as Dean can explain in Yellowknife, despite the terrors of the past, education can be a tool today for promoting understanding, dismantling systemic barriers, and advancing reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. But the damage is essential for every child coming of age to understand, and undeniable. The history is compelling.

At residential schools in Canada, tribal children faced severe penalties for perceived misbehavior, including corporal punishment, forced labor, and public humiliation. Speaking Indigenous languages or practicing cultural customs was forbidden, often resulting in beatings or isolation. These punishments aimed to suppress Indigenous identities, leaving survivors with long-term trauma. Though I saw not the slightest hint of anger or demoralization from Dean, only warmth, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada documents these abuses, highlighting the need for ongoing healing and reconciliation efforts.

The discovery of unmarked graves at former residential school sites across Canada has been a deeply shocking part of reckoning with the legacy of the residential school system. In recent years, several significant findings have come to light. For instance, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced the discovery of the remains of 215 children buried at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. This discovery was made using ground-penetrating radar (GPR). Other discoveries have found many more child graves in the residential schools, again, 4100 or more. It is a terrible thing for the First Nations people to understand that the pursuit and exploitation of natural metals and minerals across the immense Arctic barrenlands and Canadian Shield has not only created bush pilot heroes, prominent industrialists, and spectacular jewelry and furs, but also a mass-scale marginalization of the native peoples of the area.

To think that this marginalization was achieved through what was essentially kidnapping and re-education of several generations of native kids, depriving them of their traditional skills and knowledge, is a Truth that is now securely entered into the annals of educational heritage. These children were forcibly removed from their families and communities, losing not only their language and cultural practices but also essential traditional skills such as hunting, fishing, crafting, and other vital aspects of their heritage that were passed down through generations by the best teachers of the First Nations.

Teachers: this is us. Everyone who is a teacher shares this heritage as we study the methods which have contributed to our field and profession, understanding both the profound impacts of these historical injustices and the importance of integrating respect for all cultures in contemporary education.

Teachers and educational stakeholders can address historical injustices faced by Indigenous communities by educating themselves about the history and impact of residential schools, integrating Indigenous perspectives into the curriculum, and cultivating a respectful environment in every class. This includes learning about Indigenous history, participating in professional development, and incorporating Indigenous languages and traditional skills into educational programs (a movement I see all over the world). Creating a safe and supportive space for Indigenous students and promoting cultural sensitivity and awareness among students and staff are also essential. Collaborating with local Indigenous communities, inviting elders and community members to share their knowledge, and supporting reconciliation efforts are crucial steps that are underway up there. This involves supporting the calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, participating in commemorative events, and advocating for policies that promote reconciliation and healing. Ensuring equitable access to resources (the next big one is most likely to be lithium, used for car batteries), implementing anti-racism education, and advocating for educational policies that address the unique needs of Indigenous students are vital for creating an inclusive and equitable educational system.

Over the following three weeks in the Arctic, we never saw the sun set as we paddled north through the tundra and past the thin, black spruce forests, further north towards the Arctic Sea and the continuing home of the Inuit descendants. Passing eagles, moose, caribou and arctic char, Dean never left my heart and barely a single paddle stroke felt dissociated from the past and heritage of the river, the original world of birchbark and moose skin canoes, the ancient songs carried on the wind (notwithstanding the off-key songs of my fellow paddlers and me), the stories etched into the land, and the enduring spirit of those who first navigated these waters — and their children.

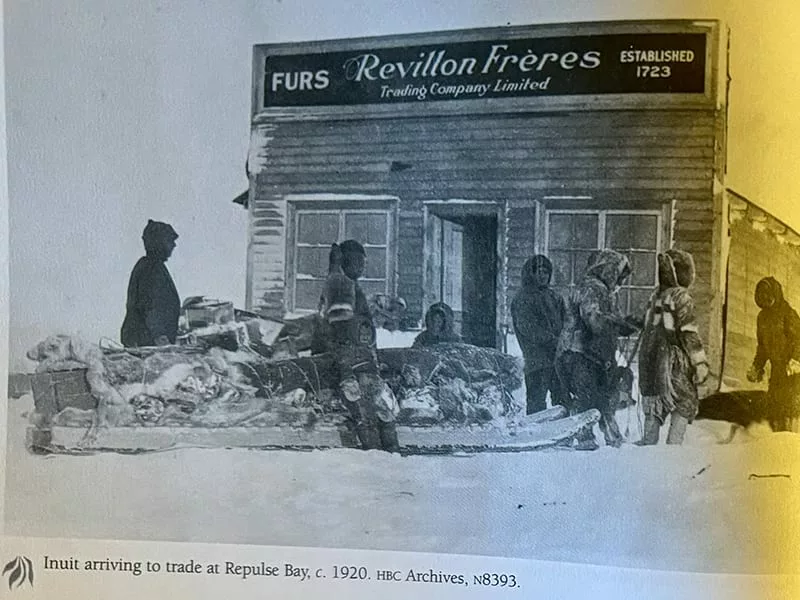

We paddle north, and I have a vague sense of heading into the heart of the old way with the natives paddling down or upriver to trade the furs they trapped for the alluring European goods hawked by outposts.

Maybe we can support the old traditions by paddling well and respecting these waters that we can still drink from.

At last, we have completed this long paddle, a float plane makes it way through a clearing in the clouds, we are back at the outfitters, and I pull an old book off the shelf. A picture. The faded photo of an old trading post — one set up by Revillon Freres Furriers, based in Paris. Their furs, once acquired from the Indigenous, traveled across the land to Quebec, and ultimately down to New York’s garment district where my own grandfather, eminent founder of Grauer Furs, selected just the finest of them, the beaver, mink, fox, checked the purity of their colors and guard hairs, their pliability, their softness; then fashioned them into New York’s finest furs; then, ultimately, in the 1960’s amidst a rising environmental movement of which I was a part, Grauer Furs being bought out by the very same Revillon Freres of Paris; my family business and heritage going away with an asset purchase that felt aggressive and foreign, and that, as a kid watching this, I thought killed my father. Then, it felt to me as I imagine the Inuit must have felt as the fur trade was drying up and the gold and diamond miners took over and blasted apart their lands for nickels and dimes.

Of course, it was not only precious pelts getting pulled out of the vast and pristine boreal forests at that time. It was the kids. I was not destined to become a furrier — I became a teacher. And Grauer Furs must have led to The Grauer School. Now I am paddling on, deep into this history, and making each paddle stroke more perfect and more quiet and it feels like a mission, like truth and reconciliation somehow.

If you ask an Indigenous person about their hat, there could be a world in response. Listen.

Bibliography

- City of Yellowknife: A Visitors Guide to Local Dene Culture Around Yellowknife.

- NWT and Nunavut Chamber of Mines. (n.d.). The geology of Yellowknife’s highways. [Newsletter].

- Morrison, William R. True North: the Yukon and Northwest Territories. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Northwest Territories, Industry, Tourism and Investment. (n.d.). [Park signage]. Yellowknife, NT.

- Northwest Territories News/North. (2024, July 15). Volume 79, Issue 12.

- Up Here. (2024, May-June). Explore Canada’s far north.

Join the Small Schools Movement!

Would you like your organization or small learning community showcased in our member spotlight? If you are not yet a member of the Small Schools Coalition, we welcome you to become a friend free of charge.

If you are already a member, contact us to discuss how we can give you the complimentary platform to show the entire world what makes your small school special!

Recent Comments